- Home

- Robert B. Parker

A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 Read online

A Catskill Eagle

( Spenser - 12 )

Robert B Parker

A Catskill Eagle

Spenser 12

By

Robert B. Parker

Copyright © 1985

For Joan

“And there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he forever flies within the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than the other birds upon the plain, even though they soar.”

HERMAN MELVILLE, Moby-Dick

CHAPTER 1

IT WAS NEARLY MIDNIGHT AND I WAS JUST getting home from detecting. I had followed an embezzler around on a warm day in early summer trying to observe him spending his ill-gotten gain. The best I’d been able to do was catch him eating a veal cutlet sandwich in a sub shop in Danvers Square across from Security National Bank. It wasn’t much, but it was as close as you could get to sin in Danvers.

I got a Steinlager from the refrigerator and opened it and sat at the counter to read my mail. There was a check from a client, a consumer protection letter from the phone company, the threat of a field collection from the electric company, and a letter from Susan.

I have no time. Hawk is in jail in Mill River, California. You must get him out. I need help too: Hawk will explain. Things are awful, but I love you.

Susan

And no matter how many times I read it, that’s all it said. It was postmarked San Jose.

I drank some beer. A drop of condensation made a shimmery track down the side of the green bottle. Steinlager, New Zealand, the label said. Probably some corruption between the Dutch eeland and the English Sealand. Language worked funny. I got off the stool very carefully and went slowly and got my atlas and looked up Mill River, California. It was south of San Francisco. Population 10,753. I drank another swallow of beer. Then I went to the phone and dialed. Vince Haller answered on the fifth ring. I said it was me. He said, “Jesus Christ, it’s twenty minutes of

I said, “Hawk’s in jail in a small town called Miller south of San Francisco. I want you to get a lawyer in there now.”

“At twenty minutes of fucking one?” Haller

“Susan’s in trouble too. I’m going out in the morning. I want to hear from the lawyer before I go.”

“What kind of trouble?” Haller said.

“I don’t know. Hawk knows. Get the lawyer down there right now.”

“Okay, I’ll call a firm we know in San Francisco. They can roust one of their junior partners out and send him down, it’s only about quarter of ten out there.”

“I want to hear from him as soon as he’s seen Hawk.”

Haller said, “You okay?”

I said, “Get going, Vince,” and hung up.

I got another beer and read Susan’s letter again. It said the same thing. I sat at the counter beside the phone and looked at my apartment.

Bookcases on either side of the front window. A working fireplace. Living room, bedroom, kitchen and bath. A shotgun, a rifle, and three handguns.

“I’ve been here too long,” I said. I didn’t like the way I sounded in the empty room. I got up and walked to the front window and looked down at Marlborough Street. Nothing was happening down there. I went back to the counter and drank some more beer. Good to keep busy.

The phone rang at four twelve in the morning. My second bottle of beer had gone flat on the counter, half finished, and I was lying on my back on the couch with my hands behind my head looking at my ceiling. I answered the phone before the third ring.

At the other end, a woman’s voice said, “Mr. Spenser?”

I said yes.

She said, “This is Paula Goldman, I’m an attorney with Stein, Faye and Corbett in San Francisco and I was asked to call you.”

“Have you seen Hawk?” I said.

“Yes. He’s in jail, in Mill River, California, on a charge of murder and assault. There’s no bail, and no realistic hope of any.”

“Who’d he kill?”

“He is accused of killing a man named Emmett Colder, who works as a security consultant for a man named Russell Costigan. There are also several accounts of assault on other security personnel and several police officers. He is apparently difficult to subdue.”

“Yes,” I said.

“He admits he killed Colder, and assaulted the various others, but says he was set up, says it was self-defense.”

“Can you make a case?”

“On the facts, maybe. But the problem is that Russell Costigan’s father is Jerry Costigan.”

“Jesus Christ,” I said.

“You know Jerry Costigan.”

“I know who he is. He owns many things.”

“Yes.” Paula Goldman’s voice was firm and unhesitant. “And one of the things he owns is Mill River, California.”

“So he doesn’t have much chance,” I said, “if he gets to trial.”

“If he gets to trial, he’s a gone goose.”

I was quiet for a minute, listening to the little transcontinental noises on the open line.

“Did he say anything about Susan Silverman?” I said.

“He said he’d come out at her request, and that they’d been waiting for him. The interview was conducted under close scrutiny and was given very grudgingly. Stein, Faye and Corbett is a major law firm in the Bay area. We have a lot of clout. If we’d had less, there might have been no interview at all.”

“That’s all you know?”

“That’s all I know.”

“What are his chances of beating this thing?”

“None.”

“Because it’s an iron-solid case?”

“Yes, it’s iron solid, but he also broke three of Russell Costigan’s front teeth. That’s like beating up Huey Long’s kid in his home parish in Louisiana in 1935.”

“Un huh.”

“And, for crissake, he’s black.”

“The Costigans are not egalitarian?”

“They are not,” she said.

“Tell me about the jail?”

“Four cells off the police station, which is in a wing of the town hall. Hawk is the only prisoner at the moment. The civilian dispatcher, female, and two cops, male, were on duty when I was there. As an officer of the court it is my obligation to remind you that abetting a jailbreak is a felony under the California penal code.”

“It’s never loosened up out there since Reagan was governor,” I said.

“When the sun comes up,” she said, “I’ll scramble around and work on the bail. But that’s shoveling shit against the tide. If you need me call the office.” She gave me the number.

I said, “Thank you, Ms. Goldman.”

She said, “Mrs. Goldman. I work criminal law fifteen, sixteen hours a day. I’m already more liberated than I want to be.”

CHAPTER 2

AT SIX FORTY-FIVE IN THE MORNING I WAS AT THE harbor health Club. Henry Cimoli had an apartment on the ground floor past the racquetball courts, and I was drinking coffee with him and making a plan.

“I thought you quit coffee,” Henry said. He was doing handstand push-ups on the beige shag wall-to-wall carpet.

“This is an emergency,” I said. I was not sleepy but I was tired. “You get the idea?”

“Sure,” Henry said. “All the years I was a trainer. I can rig any kind of cast you want. I’ll make it big, and you can slide your foot right in it when you get there.”

“We’ll need to get that little walker sole for it.” Henry eased out of the handstands. There was a chinning bar across the door to the kitchen. At five four Henry had to jump to r

each it. He began to do pull-ups, touching the back of his neck to the bar, his arms apart to the width of the doorframe.

“‘There’s a medical supply house up on Beacon Street, just past Kenmore Square. It’s on the left past the old Hotel Buckminster going toward Brookline.”

Henry was wearing gray cotton shorts and nothing else, and his body pumped up and down on the bar like a small piston. There was no suggestion of strain. His voice was normal and unforced, his movements precise and prompt.

“Maybe you should work less on strong,” I said, “and more on tall.”

Henry dropped from the pull-up bar. “Tall enough to kick you in the balls,” he said.

“Take a number,” I said, and went looking for the medical supply house.

The place didn’t open until eight. So I drank three coffees sitting in my car in front of the Dunkin‘ Donuts in Kenmore Square watching punk rockers unlimber for the day. A kid with tie-dyed hair strolled by wearing a white plastic vest and soft boots like Peter Pan. He had no shirt on and his chest was white and hairless and thin. He glanced at himself covertly in the store windows, filled with the pleasure of his outlandishness. He was probably hoping to scare a Republican, though in Kenmore Square they were sparse between ball games.

I had Susan’s letter in my shirt pocket, folded up. I didn’t read it again. I knew what it said. I knew the words. I knew the tone. The tone was frantic. I looked at my watch. Almost eight. There was a nonstop at nine fifty-five. I was packed. All I had to do was rig this leg cast with Henry and get going. I could be there by one o’clock their time. I telescoped the three paper coffee cups and got out of my car and put them in a trash can. Then I got back in and drove up and was the first customer at the medical supply house. By 9:05 Henry had the leg cast made, too big, and I was able to put it on and take it off like a fisherman’s boot. I put it in my Asics Tiger gym bag, under my clean shirts.

“You want a ride?” Henry said.

“I’ll leave the car at the airport.”

“You need any dough?”

“I got out a couple of hundred with the bank card,” I said. “That’s all there is in the account. Plus the American Express card. I can’t leave home without it.”

“You need anything,” Henry said, “you call me. Anything. You need me out there I’ll come.”

“Paul knows to call you if he can’t get me,” I said. “He’s back in school.”

Henry nodded. “Christ, you’d think you were his old man.”

“Sort of,” I said.

Henry put his hand out. I shook it. “You call me,” he said.

I headed for Logan Airport at a high speed, working against the morning traffic. If I missed the plane there were other flights, but this one was nonstop and quicker. I wanted to get there quicker.

I was twenty minutes early. I checked my bag through. If they lost it on me it would be a mess. But I couldn’t carry it on with a handgun in it. At nine fifty-five we were heading out to the runway, at ten we were banking up over the harbor and heading west.

CHAPTER 3

AT HERTZ I GOT A BUICK SKYLARK WITH THE window crank handle missing on the driver’s side. Where was O.J. when you needed him. I went straight south on 101 along the west side of the bay and at a little after three I turned off south of San Jose and headed east, on Mill River Boulevard. A mile off the highway there was a big shopping center built around a modernistic Safeway supermarket made of poured concrete, with large round windows and a broad quarry-tile apron where groceries could be loaded. A big redwood sign at the entrance to the parking lot said COSTIGAN MALL 30 Stores for Your Shopping Pleasure. The lettering was carved in the wood and painted gold. I pulled in and parked near the Safeway and got my cast from the bag. When we’d made it, Henry had rubbed it with some dirt and ashes from one of the club sand buckets. It looked a month old. In the foot, indented, was a hollow space, and I put a .25-caliber automatic in there, flat on its side. Over it I put a sponge rubber innersole. Then I took off my left shoe and slipped the cast on. I shook my pants leg down over it and got out of the car. It worked fine. Comfort was not its strong suit, but it looked right. I walked on it a little and then went in the Safeway. I bought a pint of muscatel and got directions from a customer to the town hall. Then I went back to the Buick and got in. I stashed my wallet in the glove compartment. I took a Utica Blue Sox baseball cap from my bag, messed my hair, and jammed the cap on my head. I checked in the mirror. I hadn’t shaved since yesterday morning and it was beginning to show. Strands of hair stuck out nicely under the cap and through the small opening in the back where the plastic adjustable strap was. I was wearing a white shirt and jeans. I ripped the pocket on the shirt, rolled the sleeves up unevenly, and splashed some muscatel on it. I poured more of the muscatel onto my jeans. Then I put the bottle on the seat beside me and drove on into Mill River. The town hall was white stucco and red tile roof and green lawn with a sprinkler slowly revolving, trailing the water in a slightly laggard arc behind it. There was a fire station on the left side and then a kind of connecting wing, in front of the connecting wing was a pair of blue lights on either side of a sign just like the shopping center sign, except this one said MILL RIVER POLICE. There was a small lot in front of the police station and a bigger one beyond the town hall that looked like it went around back. I turned into the big lot and circled the building. A public works garage was out back. Not stucco, cinder block. Not tile, corrugated plastic. One for show, one for blow. I could see the jail windows in the back, covered with a thick wire mesh. Two police cars were back there beside a blank door with no outside handle. I went on around the building and out the driveway past the fire station and turned toward the center of town. Fifty yards down and across the street was the town library. A sign out front said J. T. COSTIGAN MEMORIAL LIBRARY. There was a parking lot in back. I pulled in, shut off the Buick, took my bottle of muscatel and rinsed my mouth out a couple of times. The wine tasted like tile cleaner. But it smelled bad. I took the half-empty bottle, put the car keys on a window ledge behind a shrub at the rear of the library, and strolled around front. As soon as I came into public view I began to weave, my head down, mumbling to myself. It is not easy to mumble to yourself if you don’t feel moved to mumble. I didn’t know what to mumble and finally began to mumble the starting lineup for the impossible-dream Red Sox team of ‘67. “Rico Petrocelli,” I mumbled, “Carl Yastrzemski… Jerry Adair.”

I sat on the front steps of the town library and took a swig from my bottle, blocking the bottle neck with my tongue so I didn’t have to swallow any. What I was going to do didn’t get easier if I did it drunk. A couple of high school girls in leg warmers and headbands skirted me widely and went into the library.

“Dalton Jones,” I mumbled. I took another make-pretend swig.

A good-looking middle-aged woman in a lavender sweat suit and white Nikes with a lavender swoosh parked a brown Mercedes sedan in front of the library and got out with five or six books in her arms. She looked forcefully in the other direction as she edged past me.

“George Scott,” I mumbled, and as she went by I reached up and pinched her on the backside. She twitched her backside away from me and went into the library. I sipped some more muscatel and let a little slide out and along the corner of my mouth and down my chin. I could hear a small commotion at the library door behind me.

“Mike Andrews… Reggie Smith…” I blew my nose with my naked hand and wiped it across my shirt. “Hawk Harrelson… Tony C.” I raised my voice. “Jose goddamned Tartabull,” I snarled. Up at the town hall a black and white Mill River Police car turned out of the parking lot in front and cruised slowly down toward the library.

I stood and smashed the muscatel bottle against the steps.

“Joe Foy,” I said with cold fury in my voice. Then I unzipped my fly and began to take a leak on the lawn. Provocative. The cruiser pulled in beside me before I had finished and a Mill River cop in a handsome tan uniform got out and walked toward me. He wor

e a campaign hat tilted forward over the bridge of his nose like a Marine DI. “Hold it right there, mister,” he said.

I giggled. “Am holding it right there, officer.” I lurched a little and smothered a belch.

The cop was in front of me now. “Zip it up,” he snapped. “There’s women and children here.”

I zipped my fly about halfway. “Women and children first,” I said.

“You got some ID on you?” the cop said.

I fumbled at my hip pocket and then at my other hip pocket and then at my side pockets. I looked at the cop, squinting to bring him in focus.

“I wish to report a stolen wallet,” I said, speaking the words carefully like a man trying not to be drunk.

“Okay,” the cop said, “walk over to the car.” He took my arm and I went with him.

“Hands on top,” he said. “Legs apart. You’ve probably done this before.” He tapped the inside of my good ankle with his foot to force my stance out a little wider. Then he gave me a fast shakedown.

“What’s your name,” he said when he was through.

“I stop standing like this?” I said. I was resting my forehead against the roof of his car.

“Yeah. You can straighten up.”

I stayed as I was and didn’t say anything. “I asked you your name,” the cop said.

“I want lawyer,” I said.

“Who’s your lawyer?”

I rolled along the car until I had turned and was facing the cop. He was about twenty-five, nice tan. Clear blue eyes. I frowned at him.

“Sleepy,” I said. And I began to slide down the side of the car toward the ground. The cop grabbed me under the arms.

“No,” he said. “Not here. Come on, you can spend the night with us, and we’ll see in the morning.”

I let him put me in the car and drive me to the station. At twenty-two minutes to five by the clock in the station house I was in front of a cell in the Mill River jail. Booked for public drunkenness and urinating in a public place. Listed for the moment as John Doe. There was a porcelain toilet in the corner with no seat, there was a sink, and there was a concrete shelf with a mattress on it, no pillow, and a brown military blanket folded at the foot. The arresting officer opened the door to the second cell. The first was empty. There were two more beyond.

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

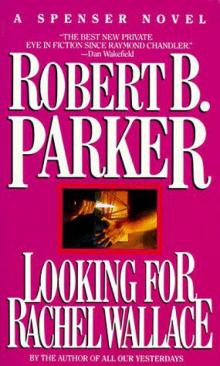

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

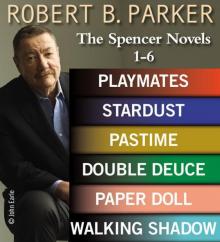

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

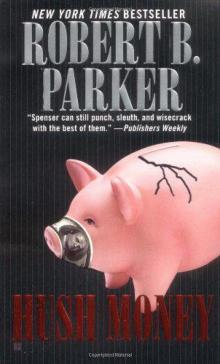

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

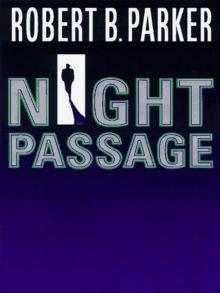

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22