- Home

- Robert B. Parker

Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Read online

Mortal Stakes

( Spenser - 3 )

Robert B Parker

Mortal Stakes

(Spenser 03)

By

Robert B. Parker

This too is for Joan, David, and Daniel

Only where love and need are one, And the work is play for mortal stakes, Is the deed ever really done For Heaven and the future’s sakes.

- ROBERT FROST

CHAPTER ONE

IT WAS SUMMERTIME, and the living was easy for the Red Sox because Marty Rabb was throwing the ball past the New York Yankees in a style to which he’d become accustomed. I was there. In the skyview seats, drinking Miller High Life from a big paper cup, eating peanuts and having a very nice time. I wasn’t supposed to be having a nice time. I was supposed to be working. But now and then you can do both.

For serious looking at baseball there are few places better than Fenway Park. The stands are close to the playing field, the fences are a hopeful green, and the young men in their white uniforms are working on real grass, the authentic natural article; under the actual sky in the temperature as it really is. No Tartan Turf. No Astrodome. No air conditioning.

Not too many pennants over the years, but no Texans either.

Life is adjustment. And I loved the beer.

The best pitcher I ever saw was Sandy Koufax, and the next best was Marty Rabb. Rabb was left-handed like Koufax, but bigger, and he had a hard slider that waited for you to commit yourself before it broke. While I shelled the last peanut in the bag he laid the slider vigorously on Thurman Munson and the Yankees were out in the eighth. While the sides changed I went for another bag of peanuts and another beer.

The skyviews were originally built in 1946, when the Red Sox had won their next-to-last pennant and had to have additional press facilities for the World Series. They were built on the roof of the grandstand between first and third.

Since the World Series was not an annual ritual in Boston the press facilities were converted to box seats. You reached them over boardwalks laid on the tar and gravel roof of the grandstand, and there was a booth up there for peanuts, beer, hot dogs, and programs and another for toilet facilities. All connected with boardwalks. Leisurely, no crowds. I got back to my seat just as the Sox were coming to bat and settled back with my feet up on the railing. Late June, sun, warmth, baseball, beer, and peanuts. Ah, wilderness. The only flaw was that the gun on my right hip kept digging into my back. I adjusted.

Looking at a ball game is like looking through a stereopticon. Everything seems heightened. The grass is greener.

The uniform whites are brighter than they should be. Maybe it’s the containment. The narrowing of focus. On the other hand, maybe it’s the tendency to drink six or eight beers in the early innings. Whatever—Alex Montoya, the Red Sox center fielder, hit a home run in the last of the eighth. Rabb fell upon the Yankee hitters in the ninth like a cleaver upon a lamb chop, and the game was over.

It was a Wednesday, and the crowd was moderate. No pushing and trampling. I strolled on down past them under the stands to the lower level. Down there it was dark and littered. A hundred programs rolled and dropped on the floor.

The guys in the concession booths were already rolling down the steel curtains that closed them off like a bunch of rolltop desks. There were a lot of fathers and kids going out. And a lot of old guys with short cigars and plowed Irish faces that seemed in no hurry to leave. Peanut shells crunched underfoot.

Out on Jersey Street I turned right. Next door to the park is an office building with an advance sale ticket office behind plate glass and a small door that says BOSTON AMERICAN LEAGUE BASEBALL CLUB. I went in. There was a flight of stairs, dark wood, the walls a pale green latex. At the top another door. Inside a foyer in the same green latex with a dark green carpet and a receptionist with stiff blue hair. I said to the receptionist, “My name is Spenser. To see Harold Erskine.” I tried to look like a short-relief prospect just in from Pawtucket. I don’t think I fooled her.

She said, “Do you have an appointment?”

I said, “Yes.”

She spoke into the intercom, listened to the answer, and said, “Go in.”

Harold Erskine’s office was small and plain. There were two green file cabinets side by side in a corner, a yellow deal desk opposite the door, a small conference table, two straight chairs, and a window that looked out on Brookline Ave. Erskine was as unpretentious as his office. He was a small plump man, bald on top. The gray that remained was cut close to his head. His face was round and red-cheeked, his hands pudgy. I’d read somewhere that he’d been a minorleague shortstop and hit.327 one year at Pueblo. That had been a while ago; now he looked like a defrocked Santa.

“Come in, Mr. Spenser, enjoy the game?”

“Yeah, thanks for the pass.” I sat in one of the straight chairs.

“My pleasure. Marty’s something else, isn’t he?”

I nodded. Erskine leaned back in his chair and cleaned the corners of his mouth with the thumb and forefinger of his left hand, drawing them together along his lower lip. “My attorney says I can trust you.”

I nodded again. I didn’t know his attorney.

Erskine rubbed his lip again. “Can I?”

“Depends on what you want to trust me to do.”

“Can you guarantee that what we say will be confidential, no matter what you decide?”

“Yes.” Erskine kept working on his lower lip. It looked clean enough to me.

“What did my lawyer tell you when he called?”

“He said you’d like to see me after today’s game and there’d be a pass waiting for me at the press entrance on Jersey Street if I wanted to watch the game first.”

“What do you charge?”

“A hundred a day and expenses. But I’m running a special this week; at no extra charge I teach you how to wave a blackjack.”

Erskine said, “I heard you were a wit.” I wasn’t sure he believed it.

“Your lawyer tell you that too?” I asked.

“Yes. He discussed you with a state police detective named Healy. I think Healy’s sister married my lawyer’s wife’s brother.”

“Well, hell, Erskine. You know all you really can know about me. The only way you can find out if you can trust me is to try it. I’m a licensed private detective. I’ve never been to jail. And I have an open, honest face. I’m willing to sit here and let you look at me for a while, I owe you for the free ball game, but eventually you’ll have to tell me what you want or ask me to leave.”

Erskine stared at me some more. His cheeks seemed a little redder, and he was beginning to develop callus tissue on his lower lip. He brought his left hand down flat on the top of the desk. “Okay,” he said. “You’re right. I got no choice.”

“It’s nice to be wanted,” I said.

“I want you to see if Marty Rabb’s got gambling connections.”

“Rabb,” I said. Snappy comebacks are one of my specialities.

“That’s right, Rabb. There’s a rumor, no, not even that, a whisper, a faint, pale hint, that Rabb might be shading a game now and then.”

“Marty Rabb?” I said. When I’ve got a good line, I like to stick with it.

“I know. It’s hard to believe. I don’t believe it, in fact.

But it’s possible and it’s got to be checked. You know what even the rumor of a fix means to baseball.”

I nodded. “If you did have Rabb in your teacup, you could make a buck, couldn’t you?”

Just hearing me say it made Erskine swallow hard. He leaned forward over the desk. “That’s right,” he said. “You can get good odds against the Sox anytime Marty pitches. If you could get that extra percentage by having Rabb on your end of the bet

, you could make a lot of money.”

“He doesn’t lose much,” I said. “What was he last year, twenty-five and six?”

“Yeah, but when he does lose, you could make a bundle. And even if he doesn’t lose, what if you’ve got money bet on the biggest inning? Marty could ease up a little at the right time. We don’t score much. We’re all pitching and defense and speed. Marty wouldn’t have to give up many runs to lose, or many runs to make a big inning. If you bet right he wouldn’t have to do it very often.”

“Okay, I agree, it would be a wise investment for someone to get Rabb’s cooperation. But what makes you think someone has?”

“I don’t quite know. You hear things that don’t mean anything by themselves. You see stuff that doesn’t mean anything by itself. You know, Marty grooving one to Reggie Jackson at the wrong time. Could happen to anyone. Cy Young probably did it too. But after a while you get that funny feeling. And I’ve got it. I’m probably wrong. I got nothing hard.

But I have to know. It’s not just the club, it’s Marty. He’s a terrific kid. If other people started to get the funny feeling it would destroy him. He’d be gone and no one would even have to prove it. He wouldn’t be able to pitch for the Yokohama Giants.”

“Hiring a private cop to investigate him isn’t the best way to keep it quiet,” I said.

“I know, you’ve got to work undercover. Even if you proved him innocent the damage would be done.”

“There’s another question there too. What if he’s guilty?”

“If he’s guilty I’ll hound him out of baseball. The minute people don’t trust the integrity of the final score, the whole system goes right down the tube. But I’ve got to know first, and I’m betting there’s nothing to it. I’ve got to have absolute proof. And it’s got to be confidential.”

“I’ve got to talk to people. I’ve got to be around the club. I can’t find out the truth without asking questions and watching.”.

“I know. We’ll have to come up with a story to cover that. I don’t suppose you play ball?”

“I was the second leading hitter on the Vine Street Hawks in nineteen forty-six.”

“Yeah, you ever stood up at the plate and had someone throw you a major-league curve ball?”

I shook my head.

“I have. Nineteen fifty-two I went to spring training with the Dodgers and Clem Labine threw about ten of them at me the first intersquad game. It helped get me into the front office. Besides you’re too old.”

“I didn’t think it showed,” I said..

“Well, I mean, for a ballplayer, starting out.”

“How about a writer?” I said.

“The guys know all the writers.”

“Not a sports reporter, a writer. A guy doing a book on baseball—you know, The Boys of Summer, The Summer Game, that stuff.”

Erskine thought about it. “Not bad,” he said. “Not bad.

You don’t look much like a writer, but hell, what’s a writer look like? Right? Why not? I’ll take you down, tell them you’re doing a book and you’re going to be hanging around the club and asking questions. It’s perfect. You know anything about writing?”

“I’ve read some,” I said.

“I mean, can you sound like a writer? You look like the bouncer at a health club.”

“I can keep from sounding as stupid as I look,” I said.

“Yeah, okay, it sounds good to me. I see no problem.

But you gotta be, for crissake, discreet. I mean dis-goddamncreet. Right?”

“I am, as we writers say, the very soul of discretion. I’ll need a press pass or whatever credentials you people issue.

And it is probably smart if you take me down and introduce me around.”

“Yeah, I’ll take care of that.” He looked at me and started working on his lip again. “This is between you and me,” he said. “No one else knows. Not the manager, not the owners, not the players, nobody.”

“How about your lawyer?” I asked.

“He is my own lawyer, not the club’s. He thinks I wanted you for personal business.”

“Okay, when do I meet the team?”

Erskine looked at his watch. “Too late today, half of them are showered and gone. How about tomorrow? We’ll go in before the game and I’ll introduce you around.”

“I’ll show up here about noon tomorrow then.”

“Yeah,” he said. “That’ll be good. You got a title for this book you’re supposed to be writing?”

“I’m looking for sales appeal,” I said. “How about The Sensuous Baseball?”

Erskine said he didn’t like that title. I went home to think of another one.

CHAPTER TWO

I GOT UP early the next morning and jogged along the river.

There were sparrows and grackles mixed in among the pigeons on the esplanade, and I saw two chickadees in the sandpit of one of the play areas. A couple of rowers were on the river, a girl in jeans tucked into high brown boots was walking two Welsh corgis, and there were some other joggers.

Near the lagoon, past the concert shell, a bum in an old blue sharkskin suit was sleeping on a newspaper, and along Storrow Drive the commuter traffic was just beginning.

I was still living at the bottom of Marlborough Street and the run up to the BU footbridge took about ten minutes. I crossed the footbridge over Storrow Drive and went in the side door of the BU gym. I knew a guy in the athletic department and they let me use the weight room. I spent forty-five minutes on the irons and another half hour on the heavy bag. By that time some coeds were passing by on their way to class and I finished up with a big flourish on the speed bag. They didn’t seem impressed.

I jogged back downriver with the sun much warmer now and the dew gone from the grass and the commuter traffic in full cry. I was back in my apartment at five of nine, glistening with sweat, and reeking of good circulation, and throbbing with appetite.

I squeezed some orange juice and drank it, plugged in the coffee, and went for a shower. At quarter past nine I was back in the kitchen again in my red and white terry-cloth robe that Susan Silverman had given me on my last birthday.

It had short sleeves and a golf umbrella on the breast pocket and the label said JACK NICKLAUS. Every time I put it on I wanted to yell “Fore.”

I drank my first cup of coffee while I made a mushroom omelet with sherry, and my second cup of coffee while I ate the omelet, along with a warm loaf of unleavened Arab bread, and read the morning Globe. When I finished, I put the dishes in the dishwasher, made the bed, and got dressed.

Gray socks, gray slacks, black loafers, and an eggshell-colored stretch knit shirt with small red hexagons all over it. I clipped my holster on over the belt on my right hip. The blue steel revolver was nicely color-coordinated with the black holster and the gray slacks. It clashed badly when I wore brown. To cover the gun I wore a gray denim jacket with red stitching along the pockets and lapels. I checked myself in the mirror.

Adorable. Lucky it wasn’t ladies’ day. I’d get molested at the park.

The temperature was in the mid-eighties and the sun was bright when I got out onto Marlborough Street. I walked a block over to Commonwealth and strolled up the mall toward Fenway Park. It was still too early for the crowd to start gathering, but the early signs of a game were there. The old guy that sells peanuts from a pushcart was pushing it along toward Kenmore Square, an old canvas over the peanuts. A middle-aged couple had parked a maroon Chevy by a hydrant near Kenmore Square and were setting up to sell balloons from the trunk. The trunk lid was up, an air tank leaned against the rear bumper, and the husband, wearing a blue and red tennis visor, was opening a large cardboard box in the trunk. Near the corner of Brookline Ave, outside the subway kiosk, a young man with shoulder-length blond hair was selling small pennants that said RED SOX in red script against a blue background. I looked at my watch: 11:40. You couldn’t see the park from Kenmore Square, but the light standards loomed up over the buildings and you knew it was

close. As I turned down Brookline Ave toward the park I felt the old feeling. My father and I used to go this early to watch the teams take infield.

I walked the two blocks down Brookline Ave, turned the corner at Jersey Street, and went up the stairs to Erskine’s office. He was in, reading what looked like a legal document, his chair tilted back and one foot on the open bottom drawer. I closed the door.

“You think of a new title for that book yet, Spenser?”

he said.

An air conditioner set in one of the side windows was humming.

“How about Valley of the Bat Boys?”

“Goddamn it, Spenser, this isn’t funny. You gotta have some kind of answer if someone asks you.”

“The Balls of Summer?”

Erskine took a deep breath, let it out, shook his head, as if there were a horsefly on it, kicked the drawer shut, and stood up. “Never mind,” he said. “Let’s go.”

As we went down the stairs, he handed me a press pass. “Keep it in your wallet,” he said. “It’ll let you in anywhere.”

A blue-capped usher at Gate A said, “How’s it going, Harold?” as we went past him. Vendors were starting to set up. A man in a green twill work uniform was unloading cases of beer onto a dolly. We went into the locker room.

My first reaction was disappointment. It looked like most other locker rooms. Open lockers with a shelf at the top, stools in front of them, nameplates above. To the right the training area with whirlpool, rubbing table, medical-looking cabinet with an assortment of tape and liniment behind the glass doors at the top. A man in a white T-shirt and white cotton pants was taping the left ankle of a burly black man who sat on the table in his shorts, smoking a cigar.

The players were dressing. One of them, a squat redhaired kid, was yelling to someone out of sight behind the lockers.

“Hey, Ray, can I be in the pen again today? There’s a broad out there gives me a beaver shot every time we’re home.”

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

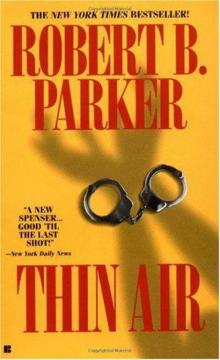

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22