- Home

- Robert B. Parker

Blue-Eyed Devil Page 2

Blue-Eyed Devil Read online

Page 2

“That’s getting to seem harder than it used to,” Virgil said.

5

THE PAY was regular at the Boston House, and the work was easy. Most people in Appaloosa had heard of Virgil Cole.

When things were slow, Virgil and I would drink coffee with the whores in the back of the room, or lean on the bar and talk with the bartenders. When the place was busy we’d move through the room, making sure nobody was heeled and, occasionally, soothing a belligerent.

I was up front one evening, talking with Willis, when one of the whores yelled for Virgil. I looked. A man in a fancy frock coat had hold of the whore’s arm and was trying to drag her out of her chair. Virgil walked over. I picked up my eight-gauge and strolled up to where I could watch Virgil’s back.

The whore’s name was Emma Scarlet. She was a pleasant whore, and I liked her.

“I’m not going with you,” she said.

“You’re selling your ass,” he said, “and my money’s as good as anybody’s.”

“You don’t like to fuck,” Emma said to the man in the frock coat. “You like to hurt people.”

“You can let her arm be,” Virgil said to the man in the frock coat.

“Who the fuck are you?” the man said.

He was tall and slim with long, blond hair and a white shirt buttoned to the neck. I didn’t see a gun.

“Virgil Cole,” Virgil said.

“What makes this your business,” the man said.

“I’m not going to fuck with this,” Virgil said. “You let her go, or I’ll kill you.”

The man let go of the whore’s arm and took a step back, as if Virgil had pushed him.

“Kill me?”

“That’s better,” Virgil said.

“Kill me?” the man said. “Over a fucking whore in a saloon?”

“Got trouble with this whore, find another one,” Virgil said.

“Some other place,” Emma said. “Nobody here’s gonna let him do anything.”

Virgil nodded.

“Any of you ladies care to do business with this gentleman?” Virgil said.

No one said anything. Several of the whores shook their heads.

“Guess not,” Virgil said to the man. “Try down the street.”

“You’re kicking me out?” the man said. “Because the whores don’t like me?”

“I am,” Virgil said, and stepped aside to let him pass.

“You got no idea who I am, do you?”

“I don’t,” Virgil said, and nodded toward the door.

“My name’s Nicholas Laird,” he said. “That mean anything to you?”

“Means none of these ladies want your business,” Virgil said.

He took hold of Laird’s right arm with his left hand. Laird tried to shake it off and couldn’t.

“We’ll walk to the door,” Virgil said.

“You’re heeled,” Laird said. “And I’m not. And you got the shotgun over there.”

“Bad odds,” Virgil said.

“Next time you see me,” Laird said, “odds are gonna be different.”

Virgil’s face changed slightly. No one else probably could tell. But I knew he was smiling.

“Maybe not,” Virgil said.

6

WE WERE DRINKING coffee at the bar with Willis

McDonough.

“Would you really have shot him?” Willis asked.

“Certain,” Virgil said.

“She’s a whore,” Willis said.

“She is,” Virgil said. “But she ain’t a slave.”

Willis nodded and looked like he didn’t get it, but he didn’t need to.

“Well, you bit a pretty big end off the plug,” Willis said. “His old man is General Horatio Laird. Took over Bragg’s place after”-Willis looked at me-“after he, ah, died. Bought that Scots bull, too.”

“Black angus,” I said.

“Yeah,” Willis said. “Them, and the cows, and made a killing with ’em. People back east was eatin’ them fast as Laird could slaughter the steers.”

“Rich man?” I said.

“Damn straight,” Willis said.

“What’s the ‘general’ for.”

“Confederate army.”

“Still hanging on to it,” I said.

“Proud of it,” Willis said. “Proud of a lot of things. But the kid ain’t one of them.”

“Nicholas,” Virgil said.

“The general must have done some bad stuff in his life, ’cause Nicholas is a big punishment,” Willis said.

Virgil didn’t seem to be listening. He scanned the room aimlessly. But I knew he heard everything. Just like he saw everything.

“Wild?” I said.

“Thinks he’s a gun hand,” Willis said. “Tell me he practices an hour every day with a Colt.”

“Ever shoot at live targets?” Virgil said.

“Heard he might,” Willis said. “ ’Specially he got some folks behind him.”

“Folks,” Virgil said.

“General’s getting on,” Willis said. “He’s tryin’ to let the kid run things, so he’ll be ready when the general steps off the train. Kid has hired himself some second-rate riffraff up there worse than Bragg had.”

“Be some bad riffraff,” Virgil said. “They shooters?”

“Most of ’em couldn’t hit a bull in the ass with a shovel,” Willis said.

“Useless, too,” Virgil said.

7

IT WAS A DARK gray day, when Amos Callico came into the saloon, with four of his policemen. The four policemen all carried Winchesters.

“Like to sit with you boys for a minute,” Callico said.

We sat at a table up front near the bar. The four policemen ranged along the walls near us. The tables around us were empty. One of the bartenders brought a bottle and three glasses.

“Understand you hired on here,” Callico said.

He poured himself some whiskey and offered the bottle toward us. Virgil and I declined.

“That right?” Callico said.

“It is,” Virgil said.

“Bouncers,” Callico said.

“Correct,” Virgil said.

“Got you a big list of rules,” Callico said, and nodded without looking at the rules posted on the wall.

“We do,” Virgil said.

“Pretty much same rules you had for the town when you was marshal,” Callico said.

“Pretty much,” Virgil said.

“Just want to be sure you remember that you ain’t marshal now,” Callico said.

“I remember,” Virgil said.

Callico looked at me for the first time.

“You?” he said.

“I remember, too,” I said.

He looked at the eight-gauge leaning against the edge of the table.

“You haul that fucking blunderbuss around with you everywhere?” he said.

“I do,” I said.

“For God’s sake, why?” Callico said.

“Same reason you have your boys carry Winchesters in a saloon,” I said. “Folks get the idea you’re serious.”

Callico looked at me without expression for a moment. Then he turned back to Virgil.

“Why do you suppose Speck hired you?” Callico said.

“Keep order,” Virgil said.

“I’m the one keeps order in Appaloosa,” Callico said.

“Well, that’s by-God comforting,” Virgil said. “We run into trouble we’ll be sure to holler for you.”

“You should have hollered for me already,” Callico said. Virgil looked at me.

“You know any reason we should have hollered for the police?” Virgil said.

“Nope.”

“You threw Nicky Laird out of here, couple days ago, for a damn whore.”

“Several damn whores,” Virgil said.

“He’s a highly regarded citizen of this town, and his father is a close personal friend of mine.”

“Nice,” Virgil said.

“Yo

u embarrassed him in public,” Callico said.

“Man embarrassed himself,” Virgil said.

“Boys,” Callico said, and poured himself more whiskey. “This is exactly why I don’t want no vigilante law enforcing going on. There’s a distinguished citizen being insulted by some whores and you side with the whores.”

He stopped, drank some of his whiskey, and shook his head slowly.

“You boys know the county sheriff’s chief deputy,” Callico said.

“Stringer,” Virgil said.

Callico nodded.

“He was in town picking up a prisoner. Got a lot of regard for you boys.”

“Stringer’s a good man,” Virgil said.

“And I got a high regard for you both. I know your reputation,” Callico said. “But you can’t run a town with two different sets of law.”

“Welcome to borrow ours,” Virgil said.

Callico slammed his hand loudly on the table. Virgil didn’t appear to notice.

“Goddamn it,” he said. “I don’t want either one of you working here. That put it plain enough?”

“I’d say it was,” he answered. “You say so, Everett?”

“I do,” I said.

“Then you’ll quit,” Callico said.

“No,” Virgil said.

“No?” Callico said. “I won’t take no.”

“Everett,” Virgil said, “I think Chief Callico is trying to intimate us…”

Virgil paused and frowned and shook his head.

“No,” he said. “That ain’t right. What am I trying to say, Everett?”

“Intimidate?” I said.

“That’s it,” Virgil said. “I think the chief is trying to intimidate us.”

As quietly as I could, I cocked both hammers on the eight-gauge.

“Goddamn it, I’m telling you plain what I want,” Callico said.

“Amos,” Virgil said. “Me ’n Everett don’t much care what you want.”

“You defying me?” Callico said.

“By God,” Virgil said. “I believe we are.”

“There’s five armed men here,” Callico said.

Virgil said nothing.

“You’re willing to die rather than let me run you off?” Callico said.

Virgil shook his head.

“Don’t expect to die,” he said.

“Against five men?” Callico said.

“Expect me and Everett can kill you all,” Virgil said.

Everyone was still, except Callico. I could hear him breathing in and out, his chest heaving slowly. Then he, too, quieted. Very slowly he put both hands flat on the tabletop.

“Don’t get ahead shooting people up in a saloon,” he said, and looked at us.

Then he stood and jerked his head at the officers along the wall.

“We’ll talk again,” he said to Virgil.

And they filed out.

“Be my guess it ain’t over,” I said.

“When he finds an excuse,” Virgil said.

8

IF WE STAYED around the house in the morning until Allie got up, she set right in cooking us breakfast. So we tried to get out, before she woke up, and went to eat at Café Paris. Since I wasn’t a lawman these days, and I didn’t expect to shoot anybody, I left the eight-gauge in the house.

“We got to eat supper with her sometimes, so’s not to hurt her feelin’s,” Virgil said. “But I can’t face her cooking in the morning.”

“How’s the rest of it going,” I said.

“She don’t seem so crazy,” Virgil said.

“Maybe ’cause she got Laurel to take care of,” I said.

“Maybe,” Virgil said.

“Makes her feel important,” I said.

“She’s important to me,” Virgil said.

“I know,” I said.

“Sex life be better, though,” Virgil said, “Allie wasn’t sleepin’ with Laurel.”

“Maybe I could arrange for Laurel and me to take long walks in the evening,” I said.

“Might help,” Virgil said.

“And,” I said, “soon as we settle in, I’ll get a place of my own.”

“I know,” Virgil said. “But I ain’t sure Laurel can sleep by herself.”

“No,” I said. “Probably can’t.”

Virgil paid for breakfast.

“So we’re back to the long walks,” I said.

We stood.

“Thing is,” Virgil said as we left Café Paris, “Allie says she feels funny doing it now that there’s a child in the house.”

“Even if the child is out for walk?” I said. “With me?”

Virgil shrugged. We strolled along Main Street to the Boston House and sat on the front porch and looked at the town.

“Be worth a try,” Virgil said.

We sat without talking. There was nothing uncomfortable in the silence. We could sit quiet for a long time. And we’d shared a lot of silences in the years we’d been together.

The land north of Appaloosa rose gradually through the mesquite. A wagon road ran up the rise to the edge of town, where it became Main Street. From town, unless you were at the very northern edge, you couldn’t see the road. It was as if Appaloosa stood long at the edge of a cliff, and when anything entered town from that direction it seemed simply to appear. There wasn’t a lot of traffic yet on Main Street. Two freight wagons appeared, each hauled by four big draft horses, their wide hooves kicking up little scatters of dust as they came. The early stage to Blue Rock went past us, heading north with two passengers and the driver up top next to the shotgun messenger.

“Town don’t bustle much,” Virgil said, “this early.”

“Later,” I said. “It’ll bustle later.”

Virgil nodded toward the north end of Main Street.

“Couple riders,” he said.

I looked.

“So?” I said.

“Recognize anybody?” Virgil said.

“Not yet,” I said.

“One on the left’ll be Pony Flores,” Virgil said.

I studied the riders.

Then I said, “I believe it will.”

9

THE RIDERS pulled up and sat their horses in front of the Boston House.

“Pony,” Virgil said.

Pony nodded at him. His Stetson was tipped forward, shading his face.

“Thought you was going to live Chiricahua for a spell,” I said.

Pony shrugged and tipped his head toward the rider beside him.

“My brother,” he said, “Kha-to-nay.”

We said, “Hello.”

Kha-to-nay had no reaction.

“He speak English?” Virgil said.

“Can,” Pony said. “Won’t.”

“Don’t like English?” Virgil said.

“He raised Chiricahua,” Pony said. “Don’t like white men.”

“He understand what we say?” I asked.

“Sure,” Pony said. “But only listen Chiricahua. Only talk Chiricahua.”

“Should introduce him to Laurel,” I said. “She only talks Virgil.”

“Chiquita,” Pony said. “She is well?”

“Doin’ fine,” Virgil said. “Kinda quiet, is all.” Kha-to-nay was motionless on his horse. As far as I could tell, watching him sit a horse, he was a little shorter than Pony, and a little wider. Pony had on buckskin leggings and high moccasins. The handle of a knife showed at the top of the right moccasin. He had on a dark blue shirt that might have once belonged to a soldier, and a big horn-handled Colt on a concho-studded belt. There was a Winchester in his saddle scabbard. Kha-to-nay wore a dark suit and a black-and-white striped shirt buttoned up tight to his neck. His black hair came to his shoulders. He, too, had a Winchester, and he wore a bowie knife on his belt.

“You lawmen again?” Pony said.

“Not at present,” Virgil said.

Pony nodded.

“Need help,” he said.

“Okay,” Virgil said.

�

��How the law in this town?” Pony said.

“Got a police chief,” I said. “Name of Amos Callico. Seems pretty set in his ways.”

Pony looked at Virgil.

“Don’t like him,” Virgil said.

“You live someplace?” Pony said.

“Got a house,” Virgil said.

“We go there and talk,” Pony said.

“Sure,” Virgil said. “Allie be glad to see you.”

We stood, and with Pony and Kha-to-nay walking their horses beside us, we went down Main Street toward Virgil’s house.

“What’s Kha-to-nay mean, in English?” I said to Pony. Pony thought a minute.

“Sees a Snake,” he said. “I think.”

“You think?” I said.

Pony pointed to his head.

“Change into Spanish,” he said. “Then Spanish to English.”

We could have been speaking Egyptian for all the attention Kha-to-nay paid. He rode silently, his eyes shifting left and right as he rode. We went down to First Street and turned right and walked a block to Front Street, where Virgil’s house was.

Allie was on the front porch in a rocker, reading to Laurel. I knew what she was reading. It was a book called Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, Fashion, and Manual of Politeness. She’d been reading a chapter a day to Laurel since we left Brimstone. I didn’t know if it was doing Laurel any good, but Allie appeared to be soaking it up.

They both looked up as we came into the small yard. Neither of them said anything for a moment. Then Laurel stood up abruptly and stepped off the porch. She walked to Pony, being careful not to look at Kha-to-nay, and took the derringer out of her apron pocket, and held it out so Pony could see it. Pony smiled, threw a leg over the pommel of his saddle, and slid fluidly off his horse.

“Chiquita,” he said.

She jumped into his arms, and he held her, rocking gently side to side. Kha-to-nay sat silent as a stone.

“Pony Flores,” Allie said. “How perfectly lovely. Come sit on the porch, you and your friend.”

Pony said something to Kha-to-nay in Apache. Kha-to-nay shook his head. Pony spoke again. Kha-to-nay did not answer, nor did he look at any of us.

“My brother is a donkey,” Pony said. “But he is my brother.”

10

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

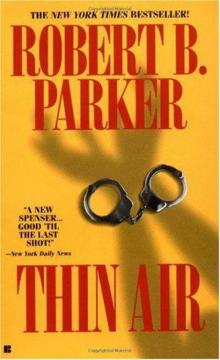

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22