- Home

- Robert B. Parker

Rough Weather Page 2

Rough Weather Read online

Page 2

“It’s the one he used last time,” I said.

“In Marshport?”

“Yeah,” I said, “two, three years ago.”

“When he helped you?”

“Yep.”

“How about when he almost killed you?”

“Yeah, he was Rugar then, too,” I said. “Almost ten years.”

Carrying his small suitcase, Rugar walked across the lawn toward us.

“Dr. Silverman,” he said to Susan. “A pleasure to see you again.”

Susan nodded without saying anything. Rugar was wearing a gray blazer, gray slacks, a gray shirt with a Windsor collar and sapphire cuff links, a charcoal tie with a sapphire tie clasp, and black shoes with pointy toes.

“Spenser,” Rugar said.

“Rugar,” I said.

He smiled.

“Our paths seem to keep crossing,” Rugar said.

“Kismet,” I said.

“I hope we are not here on conflicting missions,” Rugar said.

“Tell me what you’re here for,” I said, “and I can tell you if there’s conflict.”

Rugar smiled again. It was more of an automatic facial gesture than an expression of anything.

“You could,” Rugar said. “But you wouldn’t.”

“How do you know?” I said.

“Because I wouldn’t,” Rugar said.

“I’m not sure we’re as much alike as you think we are,” I said.

“We seemed rather alike in Marshport,” Rugar said.

“The first time we met, you almost killed me,” I said.

“But I didn’t,” Rugar said. “You almost put me in jail.”

“But I didn’t,” I said.

“So I guess we are starting even here,” Rugar said.

“You wish,” I said.

Again, the meaningless smile.

“You have never lacked for confidence,” he said.

“Never had reason to,” I said.

“And perhaps you are more playful than I,” Rugar said.

“There are viruses more playful than you are,” I said.

Rugar nodded.

“But you know as well as I do,” he said, “that the game we play has neither winners nor losers. There are only the quick and the dead.”

“I know that,” I said.

“Makes the game worth playing, perhaps.”

“Especially for the quick,” I said.

“‘Only when love and need are one . . .’” Rugar said.

“‘And the work is play for mortal stakes . . . ’?”

“You know the verse,” Rugar said.

“You assumed I would,” I said.

“I did,” Rugar said.

“We quick are a literate bunch.”

“Let us hope it continues,” Rugar said.

He nodded gravely to Susan.

“Perhaps we’ll chat again,” he said.

We watched him walk back across the lawn toward the house. Susan hugged herself.

“God,” Susan said. “It’s as if there’s a chill where he’s been.”

“If I remember right, at the depths of Dante’s Inferno,” I said, “Satan is frozen in ice.”

“It’s as if Rugar has no soul,” Susan said.

“Probably doesn’t,” I said. “Got a couple of rules, I think. But soul is open to question.”

“Does he frighten you?”

“Probably,” I said. “If I think about it. He’s pretty frightful.”

“But . . . that won’t influence what you do,” she said.

“No.”

The day had darkened. I looked up. Clouds had begun to gather between us and the sun. The day was still. There was no wind at all.

“Gee,” I said. “He really does leave a chill.”

Susan glanced up at the sky and shrugged slightly. When she was focused on something, it was hard to get her off it.

“Do you think it’s a coincidence that he’s here and you’re here?” Susan said.

“Hard to figure how it wouldn’t be,” I said.

“But do you think it is?” Susan said.

“No. I don’t think it’s a coincidence.”

“So if it isn’t,” Susan said, “what does it mean?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“So you’ll just plow along,” Susan said, “doing what you do, and awaiting developments.”

“Yuh,” I said.

6

By the time I had mastered my tuxedo and clipped on my bow tie (fashion titan though I was, I had never accomplished the art of the bow tie), the view through the tall windows was gray. The skies were dark and low. The ocean was nearly the same color and very still. It took a long stare to see the line where the horizon traced between them. There was still no wind, but there was something in the atmosphere that suggested that some wind would be along.

I had a foot up on an ivory-colored hassock and was putting a short .38 revolver into an ankle holster when Susan came down the hall in a white dress that fit her well. She looked like she was receiving an Academy Award for stunningness. I took my foot off the hassock and put it on the floor and shook the pant leg down over the gun.

“Wow!” I said.

She smiled.

“I thought much the same thing when I looked in the mirror,” she said.

“How about me?” I said.

“I thought you’d say ‘Wow!’ too,” she said.

“No, my appearance,” I said. “Don’t I remind you of Cary Grant?”

“Very much,” Susan said, “except for looking good.”

“That’s not the way you were talking an hour ago,” I said.

“An hour ago,” Susan said, “you were seducing me.”

“Which wasn’t that difficult,” I said.

“No,” she said. “It wasn’t.”

We stood together, looking out at the gathering weather.

“I thought the storm was supposed to miss us,” Susan said.

“You can’t believe the weather weenies,” I said.

“What’s left,” Susan said.

“Don’t get existential on me,” I said.

She smiled and looked at me carefully.

“You seem so unlikely a person to own his own tux,” Susan said.

“It’s hard to find my size in the rental stores,” I said.

“Or anywhere else, I would imagine,” Susan said. “Did you tie that bow tie?”

“I don’t know how,” I said. “If I bought one, could you tie it for me?”

“I don’t know how,” Susan said.

“The things you do know,” I said, “more than compensate.”

“Well, no one can tell if it’s a clip-on anyway,” she said.

We looked out the window some more.

“What is the plan?” Susan said.

“We meet in the chapel,” I said, “at four. We stay with Heidi Bradshaw, sitting in her pew during the ceremony and being handy during the reception.”

“The chapel,” Susan said.

“I think on other days it’s a library,” I said. “But Heidi’s party planner has chapelized it for today.”

Far out to sea, a vertical flash of lightning appeared fleetingly.

“Don’t see that so much,” I said. “This time of year.”

Susan nodded. Her shoulder pressed against my upper arm as we stood. There was a kind of breathlessness in the air outside the window, as if the lightning had ratcheted up the tension in the atmosphere.

“Why do you think he’s here?” Susan said.

I knew who she meant.

“He’s not a social kind of guy,” I said. “I assume it’s business.”

She nodded.

“We don’t really know quite why you’re here,” she said.

“Same answer,” I said.

“Maybe he doesn’t know, either,” Susan said.

“Maybe,” I said.

The lightning flashed again, and the leaves on some of the

trees near the house had begun trembling faintly. Susan turned suddenly against me and put her arms around me and pressed her face against my chest. It was almost unthinkable that she would hug me at such a time and mess up her outfit. I put my arms around her lightly and patted her softly.

“If he kills you,” she said, quite calmly, “I will die.”

“That would make two of us,” I said. “He won’t kill me.”

“I would die,” Susan said.

The first scatter of raindrops hit the window.

“No one’s done it yet,” I said.

“He came close ten years ago,” Susan said.

“Close only counts in horseshoes,” I said.

I patted her gently on the backside. She nodded and straightened.

“You can’t leave this alone,” she said. “Can you?”

“No,” I said.

“I understand,” she said.

“I know you do.”

“It was the gun,” she said. “Seeing you put on the gun.”

“I always wear a gun,” I said.

“I know.”

“We need to get going,” I said.

“Yes,” she said.

We stood for a bit longer with our arms around each other, while the rain became more frequent against the big window. Then Susan stepped back and looked at me and smiled.

“Here we go,” she said. “Let me just check the mirror that having a mini-breakdown hasn’t messed up my look.”

“Nothing could,” I said.

She walked to a full-length mirror at the end of the hall and studied herself for a moment.

“You know?” she said. “You’re right.”

7

As we walked the long corridor toward the chapel, I could hear the faint sound of a helicopter landing on the pad behind the house on the south side of the island. A helicopter is like a tank. Once you’ve heard one, you always remember.

“Late,” I said to Susan.

“What?”

“Chopper,” I said. “Lucky they got down before the storm starts to rumba.”

“You think the storm will get worse?”

“Yes.”

“I didn’t even hear the helicopter,” Susan said.

“That’s because you’re focused on me in my tux,” I said.

“Of course,” she said. “You’re always listening, aren’t you?”

I nodded.

“Sometimes I peek,” I said.

She looked at me sideways as we walked.

“I’m aware of that,” she said.

Behind us, lightning spilled briefly into the hall through the big French doors. A few seconds later there was a grumble of thunder.

“Storm’s still a ways off,” I said.

“Something about the time between the lightning and the thunder?” Susan said.

“Lightning’s traveling at the speed of light,” I said. “Thunder’s coming at the speed of sound. The closer they are, the more they coincide.”

“My God, Holmes,” Susan said in her lowest voice. “Is there no limit to your knowledge?”

“I’ve never quite been able to answer, ‘What does a woman want?’”

Susan smiled and banged my shoulder lightly with her head. In a small anteroom to the former library, Heidi and her daughter stood with Maggie Lane. With them was the famous conductor with the tan and the silver hair. Heidi was in her imperious mode. She introduced us quite formally. Actually, she introduced me, and I introduced Susan. Did Susan not notice? . . . Fat chance!

Adelaide was in full wedding dress, except there was no train. Probably couldn’t find train carriers. She had a small face, which looked even smaller because she had so much red hair insufficiently contained by her veil.

“Adelaide’s father chose not to attend,” Heidi said. “Leopold will be taking Adelaide down the aisle.”

“Okay,” I said.

“You’ll wait here with us, Mr. Spenser,” Heidi said. “Dr. Silverman, an usher will take you to the first row on the right. Mr. Spenser will join you. Please sit at the far end, near the wall.”

“Okay,” I said.

I was in my docile mode. Susan winked at me and followed the usher out of the anteroom. Through the window behind me, lightning flashed again. And not very long after, the thunder grumbled. No one paid any attention.

“You’ll be the last to enter the room, Mr. Spenser, after Leopold has delivered Adelaide to her husband. Please try to be unobtrusive.”

“On little cat’s feet,” I said.

I doubt that Heidi even heard me.

“Mo-th-er,” Adelaide said, making it into several syllables. “Everyone’s here. It’s time to start.”

Heidi was nodding absently. The anteroom door had a small peephole in it that allowed you to see into the chapel. Heidi appeared to be counting the house.

“Why does the library door have a peephole?” I said. “Keep people from stealing the books?”

“When it was built it was thought to add a secretive medieval quality,” Maggie Lane said.

I nodded. I could hear the string ensemble playing appropriate music as the guests were escorted in.

After a time, Heidi said, “All right, I’ll go.”

She looked at her daughter.

“Let me get seated before you and Leopold begin,” Heidi said. “Just like we rehearsed. Maggie, don’t let them start too soon.”

“Mo-th-er . . .” Adelaide said.

Heidi smiled and stepped away from the peephole. Heidi leaned forward and kissed her daughter, carefully, no messing up the look.

“It’ll be perfect,” she said to Adelaide.

She put her hand on Adelaide’s cheek for a moment. Then she turned and went out the other anteroom door into the hall. I took her place peeking through the door, and watched her appear a moment later at the double doors to the chapel. She came down the aisle alone, the mother of the bride, like a queen at her coronation. She was erect, beautiful, elegantly dressed, and perfectly done, with just the right amount of hip swing. I felt sort of bad for the anticlimactic Adelaide.

Maggie wanted to peek, too, and I sensed her resentment. But my docile mode took me only so far. After Heidi’s long promenade, she slipped into her seat in the first pew. I could almost feel the impulse to applaud run through the chapel, but everyone fought it off successfully.

“Okay,” I said.

“Okay,” Maggie said, as if trying to void any usurpation of her position.

Leopold put his arm out. Adelaide, looking pallid and swallowing often, put her hand on his arm. He patted it and they went out of the anteroom. I followed them discreetly. They went through the big entrance to the chapel. The musicians, cued from the anteroom, I assumed, by the grim and ubiquitous Maggie, began to play “Here Comes the Bride.” Leopold and Adelaide started down the aisle toward the waiting groom. Adelaide seemed pulled in upon herself, smaller than her mother, somehow frail-looking, as if the support of Leopold’s arm was more than symbolic. After they got to the waiting groom and Leopold had retired to his pew, I skirted the back row more silently than the yellow fog, and went down along the side and sat where I’d been told.

8

It may have begun the day as a library, and it might be a library tomorrow, but at this moment it was every inch a chapel. The ceiling had been draped in dark gauze so that it seemed to reach a peak. The seating was in real pews, not folding chairs. There were hymnals in each pew. A small program lay on the seat in each place. The bookcases were draped in the same dark gauze they’d hung from the ceiling, and stained-glass windows hung in place. The lighting was provided by candles. In front was an altar of ornately carved wood that looked as if it had been lifted from a medieval church in Nottingham. There were flowers everywhere, huge vases as tall as I was, standing in exactly the right places, hanging flowers, flowers smothering the altar.

In the back-left corner of the room a string trio supplied the music. Around the room were people I recognized. A

famous movie couple, an actor from New York, a tennis player, two senators. A lot of the women were good-looking; money always seems to help in that area. Everyone was dressed to the teeth. Like me. A hint of expensive perfume, nearly extinguished by the smell of the flowers, drifted through the room. I did not see the Gray Man. Susan was looking through the program.

“Bride’s name is Van Meer,” Susan whispered. “Her father must be the second husband, Peter Van Meer.”

I nodded.

“Do I look better in my tux than the groom?” I whispered to Susan.

“No,” she whispered back.

“Do too,” I whispered.

Susan put her finger to her lips and nodded toward the altar. The minister was there in full high-church regalia, holding a prayer book open in his hands. He began the familiar recitation.

“Dearly beloved . . .”

The room was windowless for the wedding. But through the muffling gauze, and over the minister’s orotund voice, I heard the crack of thunder. Some people in the chapel jumped slightly at the sound. The storm was very close. In fact, it might have arrived. But it was remote from the ceremony, shielded as we were by walls and curtains, gauze, and wealth. The ceremony proceeded just as if there were no storm.

“. . . you may kiss the bride,” the minister said.

They kissed. Neither husband nor wife seemed terribly enthusiastic about it. There was a slight rustle of movement at the back. Someone had arrived, quite probably by helicopter. Six men came in, wearing wet raincoats. Three went left and three went right.

And as they spread out, Rugar appeared with no coat, his gray suit perfectly dry except for the cuffs of his pants. His shoes were wet. They squished faintly as he began to walk down the center aisle toward the bride and groom. The six men took automatic weapons from under their raincoats. I had an impulse toward my ankle holster and realized it was a bad idea in a room crowded with wedding guests, and six guys with MP9s. The minister hadn’t noticed the submachine guns yet. He was looking at Rugar with contained annoyance.

“Excuse me, sir,” the minister said to Rugar, “but I would prefer . . .”

Rugar took out a handgun, it looked like a Glock, and shot the minister in the center of the forehead. The minister fell backward onto the floor in front of the altar. He convulsed a little and then lay still. Rugar turned toward the congregation, holding the Glock comfortably at his side. He was wearing a beautifully cut gray suit, a gray shirt, and a silver silk tie.

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

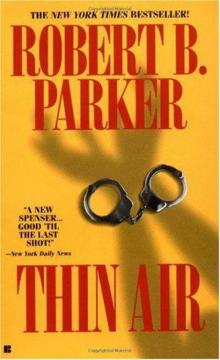

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22