- Home

- Robert B. Parker

Early Autumn s-7 Page 3

Early Autumn s-7 Read online

Page 3

Patty Giacomin said, “Paul, you know Stephen. Stephen, this is Mr. Spenser. Stephen Court”

Stephen put out his hand. It was manicured and tanned. St Thomas, no doubt His handshake was firm without being strong. “Good to see you,” he said.

He didn’t say anything to Paul and Paul didn’t look at him. Patty said, “Would you join us for a drink, Mr. Spenser?”

“Sure,” I said. “Have any beer?”

“Oh, dear, I’m not sure,” she said, “Paul, go look in the refrigerator and see if there’s any beer.”

Paul hadn’t taken his coat off. He went over to the TV set in the bookcase and turned it on, set no channel, and sat down in a black Naugahyde armchair. The set warmed up and a Brady Bunch rerun came on. It was loud.

Patty Giacomin said, “Paul, for God’s sake,” and lowered the volume. While she did that I went into the kitchen on my right and found a can of Schlitz in the refrigerator. There were two more with it, and not much else. I went back into the living room with my beer. Stephen was sitting again, sipping his martini, his legs arranged so as not to ruin the crease in his pants. Patty was standing with her martini in hand.

“Did you have much trouble finding Paul, Mr. Spenser?”

“No,” I said. “It was easy.”

“Did you have trouble with his father?”

“No.”

“Have some cheese and a cracker,” she said. I took some. Boursin on a Triscuit isn’t my favorite, but it had been a long time since breakfast I washed it down with the beer. There was silence except for a now softened Brady Bunch.

Stephen took a small sip of his martini, leaned back slightly, brushed a tiny fleck of something from his left lapel, and said, “Tell me, Mr. Spenser, what do you do?” I heard an overtone of disdain, but I’m probably too sensitive.

“I’m a disc jockey at Regine’s,” I said. “Haven’t I seen you there?”

Patty Giacomin spoke very quickly. “Mr. Spenser,” she said, “could I ask you a really large favor?”

I nodded.

“I, well, I know you’ve already done so much bringing Paul back, but, well, it’s just that it happened much sooner than I thought it would and Stephen and I have a dinner reservation… Could you take Paul out maybe to McDonald’s or someplace? I’ll pay of course.”

I looked at Paul. He was sitting, still with his coat on, staring at The Brady Bunch. Stephen said, “There’s a rather decent Chinese restaurant in town, Szechuan and Mandarin cooking.”

Patty Giacomin had taken her purse off the mantel and was rummaging in it “Yes,” she said. “The Yangtze River. Paul can show you. That’s a good idea. Paul always likes to eat there.” She took a twenty out of her purse and handed it to me. “Here,” she said. “That should be enough. It’s not very expensive.”

I didn’t take the twenty. I said to Paul, “You want to go?” and then I shrugged at the same time he did.

“What are you doing?” he said.

“Practicing my timing,” I said. “Your shrug is so expressive I’m trying to develop one just like it. You want to go get something to eat?”

He started to shrug, stopped, and said, “I don’t care.”

“Well, I do,” I said. “Come on. I’m starving.”

Patty Giacomin still held the twenty out. I shook my head.

“You asked for a favor,” I said. “You didn’t offer to hire me. My treat.”

“Oh, Spenser,” she said, “don’t be silly.”

“Come on, kid,” I said to Paul. “Let’s go. I’ll dazzle you with my knowledge of Oriental lore.”

The kid shifted slightly. “Come on,” I said. “I’m hungry as hell.”

He got up. “What’s the latest you’ll be home,” he said to his mother.

“I’ll be home before twelve,” she said.

Stephen said, “Good meeting you, Spenser. Good seeing you, Paul.”

“Likewise I’m sure,” I said. We went out.

When we were in the car again Paul said, “Why’d you do it?”

“What, agree to take you to dinner?”

“Yes.”

“I felt bad for you,” I said.

“How come?”

“Because you came home after being missing and no one seemed glad.”

“I don’t care.”

“That’s probably wise,” I said. “If you can pull it off.” I turned out of Emerson Road. “Which way?” I said.

“Left,” he said.

“I don’t think I could pull it off,” I said.

“What?”

“Not caring,” I said. “I think if I got sent off to eat with a stranger my first night home I’d be down about it”

“Well, I’m not,” he said.

“Good,” I said. “You want to eat in this Chinese place?”

“I don’t care,” he said.

We came to a cross street “Which way?” I said.

“Left,” he said.

“That the way to the Chinese restaurant?” I said.

“Yes.”

“Good, we’ll eat there.”

We drove through Lexington, along dark streets that were mostly empty. It was a cold night People were staying in. Lexington looks like you think it would. A lot of white colonial houses, many of them original. A lot of green shutters. A lot of bull’s-eye glass and small, paned windows. We came into the center of town, the green on the right. The statue of the Minuteman motionless in the cold. No one was taking a picture of it.

“It’s over there,” Paul said, “around that square.”

In the restaurant Paul said, “How come you wouldn’t let her pay for it?”

“It didn’t seem the right thing to do,” I said.

“Why not? Why should you pay? She’s got plenty of money.”

“If we order careful,” I said, “I can afford this.”

The waiter came. I ordered a Beck’s beer for me and a Coke for Paul. We looked at the menu.

“What can I have?” Paul said.

“Anything you want,” I said. “I’m very successful.”

We looked at the menu some more. The waiter brought the beer and the Coke. He stood with his pencil and paper poised. “You order?” he said.

“No,” I said. “We’re not ready.”

“Okay,” he said, and went away.

Paul said, “I don’t know what to have.”

I said, “What do you like?”

He said, “I don’t know.”

I nodded. “Yeah,” I said, “somehow I had a sense you might say that.”

He stared at the menu.

I said, “How about I order for both of us?”

“What if you order something I don’t like?”

“Don’t eat it.”

“But I’m hungry.”

“Then decide what you want.”

He stared at the menu some more. The waiter wandered back. “You order?” he said.

I said, “Yes. We’ll have two orders of Peking ravioli, the duck with plum sauce, the moo shu pork, and two bowls of white rice. And I’ll have another beer and he’ll have another Coke.”

The waiter said, “Okay.” He picked up the menus and went away.

Paul said, “I don’t know if I’ll like that stuff.”

“We’ll find out soon,” I said.

“You gonna send my mother a bill?”

“For the meal?”

“Yes.”

“No.”

“I still don’t see why you want to pay for my dinner.”

“I’m not sure,” I said. “It has to do with propriety.”

The waiter came and plunked the ravioli on the table and two bottles of spiced oil.

“What’s propriety?” Paul said.

“Appropriateness. Doing things right.”

He looked at me without any expression.

“You want some raviolis?” I said.

“Just one,” he said, “to try. They look gross.”

“I thought

you liked to eat here.”

“My mother just said that. I never been here.”

“Put some of the oil on it,” I said. “Not much. It’s sort of hot.”

He cut his ravioli in two and ate half. He didn’t say anything but he ate the other half. The waiter brought the rest of the food. We each ate four of the raviolis.

“You put the moo shu in one of these little pancakes, see, like this. Then you roll it up, like this. And you eat it.”

“The pancake doesn’t look like it’s cooked,” Paul said.

I ate some moo shu pork. He took a pancake and did as I’d showed him.

I said, “You want another Coke?”

He shook his head. I ordered another beer.

“You drink a lot?”

“No,” I said. “Not as much as I’d like.”

He speared a piece of duck with his fork and was trying to cut it on his plate.

“That’s finger food,” I said. “You don’t have to use your knife and fork.”

He kept on with the knife and fork. He didn’t say anything. I didn’t say anything. We finished eating at seven fifteen. We arrived back at his house at seven thirty. I parked and got out of the car with him.

“I’m not afraid to go in alone,” he said.

“Me either,” I said. “But it’s never any fun going into an empty house. I’ll walk in with you.”

“You don’t need to,” he said. “I’m alone a lot.”

“Me too,” I said.

We walked to the house together.

CHAPTER 6

It was Friday night, and Susan Silverman and I were at the Garden watching the Celtics and the Phoenix Suns play basketball. I was eating peanuts and drinking beer and explaining to Susan the fine points of going back door. I was having quite a good time. She was bored.

“You owe me for this,” she said. She had barely sipped at a paper cup of beer in one hand. There was a lipstick half moon on the rim.

“They don’t sell champagne by the paper cup here,” I said.

“How about a Graves?”

“You want me to get beat up,” I said. “Go up and ask if they sell a saucy little white Bordeaux?”

“Why is everyone cheering?” she said.

“Westphal just stuffed the ball backward over his head, didn’t you see?”

“He’s not even on the Celtics.”

“No, but the fans appreciate the shot. Besides, he used to be.”

“This is very boring,” she said.

I offered my peanuts to her. She took two.

“Afterwards I’ll let you kiss me,” I said.

“I’m thinking better of the game,” she said.

Cowens hit an outside shot.

“How come most of the players are black?” Susan said.

“Black man’s game,” I said. “Hawk says it’s heritage. Says there were a lot of schoolyards in the jungle.”

She smiled and sipped at the beer. She made a face. “How can you drink so much of this stuff?” she said.

“Practice,” I said. “Years of practice.”

Walter Davis hit a jump shot.

“What were you saying before about that boy you found Wednesday? What’s his name?”

“Paul Giacomin,” I said.

“Yes,” Susan said. “You said you wanted to talk about him.”

“But not while I’m watching the ball game.”

“Can’t you watch and talk at the same time? If you can’t, go buy me something to read.”

I shelled a peanut. “I don’t know,” I said. “It’s just that I keep thinking about him. I feel bad for him.”

“There’s a surprise.”

“That I feel bad for him?”

“You’d feel bad for Wile E. Coyote,” Susan said.

Westphal hit a left-handed scoop shot. The Celtics were losing ground.

“The kid’s a mess,” I said. “He’s skinny. He seems to have no capacity to decide anything. His only firm conviction is that both his parents suck.”

“That’s not so unusual a conviction for a fifteen-year-old kid,” Susan said. She took another peanut.

“Yes, but in this case the kid may be right.”

“Now you don’t know that,” Susan said. “You haven’t had enough time with them to make any real judgment.”

The Suns had scored eight straight points. The Celtics called time out.

“Better than you,” I said. “I been with the kid. His clothes aren’t right and they don’t fit right. He doesn’t know what to do in a restaurant. No one’s ever taught him anything.”

“Well, how important is it to know how to behave in a restaurant?” Susan said.

“By itself it’s not important,” I said. “It’s just an instance, you know? I mean no one has taken any time with him. No one has told him anything, even easy stuff about dressing and eating out. He’s been neglected. No one’s told him how to act.”

The Celtics put the ball in play from midcourt. Phoenix stole it and scored. I shook my head. Maybe if Cousy came out of retirement.

Susan said, “I haven’t met this kid, but I have met a lot of kids. It is, after all, my line of work. You’d be surprised at how recalcitrant kids this age are about taking guidance from parents. They are working through the Oedipal phase, among other things, often they look and act as if they haven’t had any care, even when they have. It’s a way to rebel.”

The Celtics threw the ball away. The Suns scored.

I said, “Are you familiar with the term blowout?”

“Is it like a burnout?” she said.

“No, I mean the game. You are witnessing a blowout,” I said.

“Are the Celtics losing?”

“Yes.”

“Want to leave?”

“No. It’s not just who wins. I like to watch the way they play.”

She said, “Mmm.”

I got another bag of peanuts and another beer. With five minutes left the score was 114 to 90. I looked up at the rafters where the retired numbers hung.

“You should have seen it,” I said to Susan.

“What?” She brushed a peanut shell from her lap. She was wearing blue jeans from France tucked into the tops of black boots.

“Cousy and Sharman, and Heinsohn and Lostcutoff and Russell Havlicek, Sanders, Ramsey, Sam Jones, and K. C. Jones, Paul Silas and Don Nelson. And the war they’d have with the Knicks with Al McGuire on Cousy. And Russell against Chamberlain. You should have seen Bill Russell.”

She said, “Yawn.” The sleeves of her black wool turtleneck were pushed up on her forearms and the skin of her forearms was smooth and white in contrast. On a gold chain around her neck was a small diamond. She’d removed her engagement ring when she’d gotten divorced and had the stone reset She’d had her hair permed into a very contemporary bunch of small Afro-looking curls. Her mouth was wide and her big dark eyes hinted at clandestine laughter.

“On the other hand,” I said, “Russell ought to see you.”

“Gimme a peanut,” she said.

The final score was 130 to 101 and the Garden was nearly empty when the buzzer sounded. It was nine twenty-five. We put on our coats and moved toward the exits. It was easy. No pushing. No shoving. Most people had left a long time ago. In fact most people hadn’t come at all.

“It’s a fine thing that Walter Brown’s not around to see this,” I said. “In the Russell years you had to fight to get in and out”

“That sounds like a good time,” Susan said. “Sorry I missed it.”

On Causeway Street, under the elevated, it was very cold. I said, “You want to walk up to The Market? Or shall we go home?”

“It’s cold,” Susan said. “Let’s go home to my house and I’ll make us a goodie.” She had the collar of her raccoon coat turned up so that her face was barely visible inside it

The heater in my MG took hold on Route 93 and we were able to unbutton before we got to Medford. “The thing about that kid,” I said, “is tha

t he’s like a hostage. His mother and father hate each other and use him to get even with each other.”

Susan shook her head. “God, Spenser, how old are you? Of course they do that Even parents who don’t hate each other do that Usually the kids survive it”

“This kid isn’t going to survive it,” I said, “He’s too alone.”

Susan was quiet

“He hasn’t got any strengths,” I said. “He’s not smart or strong or good-looking or funny or tough. All he’s got is a kind of ratty meanness. It’s not enough.”

“So what do you think you’ll do about it?” Susan said.

“Well, I’m not going to adopt him.”

“How about a state agency. The Office for Children, say, or some such.”

“They got enough trouble fighting for their share of federal funds. I wouldn’t want to burden them with a kid.”

“I know people who work in human services for the state,” Susan said. “Some are very dedicated.”

“And competent?”

“Some.”

“You want to give me a percentage?”

“That are dedicated and competent?”

“Yeah.”

“You win,” she said.

We turned onto Route 128. “So what do you propose,” Susan said.

“I propose to let him go down the tube,” I said. “I can’t think of anything to do about it.”

“But it bothers you.”

“Sure, it bothers me. But I’m used to that too. The world is full of people I can’t save. I get used to that. I got used to it on the cops. Any cop does. You have to or you go down the tube too.”

“I know,” Susan said.

“On the other hand I may see the kid again.”

“Professionally?”

“Yeah. The old man will take him again. She’ll try to get him back. They’re too stupid and too lousy to let this go. I wouldn’t be surprised if she called me again.”

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

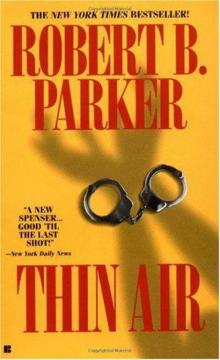

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22