- Home

- Robert B. Parker

Stone Cold js-4 Page 3

Stone Cold js-4 Read online

Page 3

“I’m here to cook you

supper,” Jenn said when she

arrived at Jesse’s condo with a large shopping bag.

“Cook?” Jesse said.

“I can cook,” Jenn said.

“I didn’t know that,” Jesse said.

“I’ve been taking a course,”

Jenn said and set the shopping bag

down on the counter in Jesse’s kitchen. “Perhaps you could make us

a cocktail?”

“I could,” Jesse said.

Jenn took a small green apron out of the shopping bag and tied it on.

“Serious,” Jesse said.

“Dress for success,” Jenn said and smiled at him.

Jesse made them martinis. Jenn put some grilled shrimp and mango

chutney on a glass plate. They took the drinks and the hors d’oeuvres to the living room and sat on Jesse’s sofa and looked out

the slider over Jesse’s balcony to the harbor beyond.

“It’s pretty here, Jesse.”

“Yes.”

“But it’s so … stark.”

“Stark?”

“You know, the walls are white. The tabletops are bare. There’s

no pictures.”

“There’s Ozzie,” Jesse said.

Jenn looked at the big framed color photograph of Ozzie Smith, in midair, stretched parallel to the ground, catching a baseball.

“You’ve had that since I’ve

known you.”

“Best shortstop I ever saw,” Jesse said.

“You might have been that good, if you hadn’t gotten

hurt.”

Jesse smiled and shook his head.

“I might have made the show,” Jesse said.

“But I wouldn’t have

been Ozzie.”

“Anyway,” Jenn said. “One

picture of a baseball player is not

interior decor.”

“Picture of you in my bedroom,” Jesse said. “On the

table.”

“What do you do with it if you have a sleepover?”

“It stays,” Jesse said.

“Sleepovers have to know about

you.”

“Is that in your best interest?” Jenn said. “Wouldn’t it

discourage sleeping over.”

“Maybe,” Jesse said.

“But not entirely,” Jenn said.

“No,” Jesse said. “Not

entirely.”

They were silent, thinking about it. Jesse got up and made another shaker of martinis.

“What is it they have to know about me?”

Jenn said when he

brought the shaker back.

“That I love you, and, probably, am not going to love

them.”

“Good,” Jenn said.

“Good for who?” Jesse said.

“For me at least,” Jenn said. “I

want you in my

life.”

“Are you sure divorcing me is the best way to show that?”

“I can’t imagine a life without you in it.”

“Old habits die hard,” Jesse said.

“It’s more than a habit, Jesse.

There’s some sort of connection

between us that won’t break.”

“Maybe its because I don’t let it

break,” Jesse

said.

“You don’t,” Jenn said.

“But then here I am.”

“Here you are.”

“I could have been a weather girl in Los Angeles, or Pittsburgh

or San Antonio.”

“But here you are,” Jesse said.

“You’re not the only one hanging

on,” Jenn said.

“What the hell is wrong with us?” Jesse said.

Jenn put her glass out. Jesse freshened her drink.

“Probably a lot more than we know,” Jenn said. “But one thing I

do know: we take it seriously.”

“What?”

“Love, marriage, relationship, each other.”

“Which is why we got divorced and started fucking other people,”

Jesse said. “Or vice versa.”

“I deserve the vice versa,” Jenn said.

“But I don’t keep

deserving it every time we talk.”

“I know,” Jesse said.

“I’m sorry. But if we take it so

seriously, why the hell are we in this mess.”

“Because we wouldn’t let it

slide,” Jenn said. “Because you

wouldn’t accept adultery. Because I wouldn’t accept suffocation.”

“I loved you very intensely,” Jesse said.

There was half a drink left in the shaker. Jesse added it to his

glass.

“You loved your fantasy of me very

intensely,” Jenn said, “and

kept trying to squeeze the real me into that fantasy.”

Jesse stared at the crystalline liquid in his glass. Jenn was still. Below them the harbor master’s launch pulled away from the

town pier and began to weave through the stand of masts going somewhere, and knowing where.

“That you talking or the shrink?” Jesse said.

“It’s a conclusion we reached

together,” Jenn

said.

Jesse hated all the circumlocutions of therapy. He sipped the lucid martini.

“Why do you think I’m so

wonderful?” Jenn said.

“Because I love you.”

Jenn was quiet. She smiled slightly as if she knew something Jesse didn’t know. It annoyed him.

“What the fuck is wrong with that?” he said.

“Think about it,” Jenn said.

“Think about shit,” Jesse said.

“Just because you’re getting

shrunk doesn’t mean you have to shrink me.”

“You think I’m wonderful because you love me?”

“Yes.”

They were both quiet. Jesse stared at her defiantly. Jenn looking faintly quizzical.

After a time, Jenn said, “Not the other way around?”

Jesse nodded slowly as if to himself, then got up and mixed a new martini.

9

Jesse’s hangover was relentless on Monday morning.

He sat behind

his desk sipping bottled water and trying to concentrate on Peter Perkins.

“We spent two days going over that guy’s apartment,” Perkins

said. “We didn’t even find anything

embarrassing.”

“And him a stockbroker,” Jesse said.

“So what do you

know?”

Perkins looked down at his notebook.

“Kenneth Eisley, age thirty-seven, divorced, no children. Works

for Hollingsworth and Whitney in Boston. Parents live in Amherst.

They’ve been notified.”

“You do that?”

“Molly,” Peter Perkins said.

“God bless her,” Jesse said.

“Coroner’s through with him,”

Perkins said. “Parents are coming

tomorrow to claim the body. You want to talk to them?”

“You do it,” Jesse said.

“You pulling rank on me?” Perkins said.

“You bet,” Jesse said. “How

about the ex-wife?”

“She lives in Paradise,” Perkins said.

“On Plum Tree Road.

Probably kept the house when they split.”

“Seen her yet?”

“No. Hasn’t returned our calls.”

“I’ll go over,” Jesse said.

“Swell,” Perkins said. “I get to

question the grieving parents,

you talk to the ex-wife, who is probably delighted.”

“Not if she was getting alimony,” Je

sse said.

“That’s cynical,” Peter Perkins

said.

“It is,” Jesse said.

“What’s the ME say?”

“Nothing special. Shot twice in the chest at close range. Two

different guns.”

“Two guns?”

“Yep. Both twenty-twos.”

“Which one killed him?”

“Both.”

“Equally?”

“Either shot would have done it. They both got him in the heart.

You want all the details about what got penetrated and stuff?”

“I’ll read the report. We figure two shooters?”

“Can’t see why one guy would shoot someone with two guns,”

Perkins said.

“Any way to tell which one shot first?”

“Not really. Far as the ME could tell they entered the victim

more or less the same time.”

“Both at close range,” Jesse said.

“Both at close range.”

“Both in the heart,” Jesse said.

Perkins nodded. “Gotta be two people,” he said.

“Or one person who wants us to think he’s two people,” Jesse

said.

Perkins shrugged.

“Pretty elaborate,” Perkins said.

“And it gives us twice as many

murder weapons.”

Jesse drank more spring water. He didn’t say anything.

“We got his phone records,” Perkins said.

“Anthony and Suit are

chasing that down.”

“Debt?” Jesse said.

“Not so far. Got ten grand in his checking account.

Got a mutual

fund worth couple hundred thousand. I’m telling you, we’ve got

nada.”

“Somebody killed him and they had a

reason,” Jesse said. “Talk

to people where he worked?”

“No. I was going to ask you. Should I call, or go in to

Boston.”

“Go in,” Jesse said.

“It’s harder to brush you off.”

“You did a

lot of this in LA,” Perkins said. “You got any ideas.”

“When in doubt,” Jesse said,

“cherchez la ex-wife.”

“Wow,”

Perkins said, “it’s great working with a pro.”

10

She was taking the photographs of Kenneth Eisley down from the big oak-framed corkboard in the office.

“Leave that head shot,” he said.

“Memories?” she said.

“Trophy,” he said.

She smiled, and handed him the pile of discarded pictures.

“Shred these,” she said. “While

I put up the new

pictures.”

He began to feed the discarded photographs through the shredder.

“What is our new friend’s name?”

she said.

“Barbara Carey,” he said.

“Forty-two years old, married, no

children. Her husband’s name is Kevin. She’s a loan officer at the

in-town branch of Pequot. He’s a lawyer in Danvers.”

“They happy?”

“What’s happy?” he said.

“They go out every Saturday night,

usually with friends. They go to brunch a lot of Sundays. The second picture up, they’re coming out of the Four Seasons.

They

don’t fight in public. They both drink, but neither one seems to be

a drunk.”

“They own a dog?” she said.

“No sign,” he said. “I think

they’re too busy being successful

young professionals to get tied down by a dog.”

“That’s good,” she said.

“I still feel worried about Kenny’s

dog.”

She glanced at the remaining photograph of Kenneth Eisley.

“Somebody will find the dog and adopt him,” he

said.

“I hope so,” she said. “Dogs are

nice.”

He fed the last photograph into the shredder.

“Kevin usually leaves the house first in the morning,” he said.

“She leaves about a half hour later, at eight-thirty.”

“That means she’s home alone for half an hour every weekday

morning.”

“Yes, but it’s a neighborhood where

everyone is home looking out

the window,” he said.

“So where will we be able to do it?”

“She does the food shopping,” he said.

“At the Paradise Mall,” she said.

She pinned the last of the pictures onto the corkboard with a small red map tack, then stepped back beside him and the two of them looked at thirty-five photographs of Barbara Carey going about the business of her public life.

“Big parking lot,” he said. “At

the Paradise

Mall.”

11

Molly Crane had a pretty good body, Jesse thought, for a cop with three kids. The gun belt always looked too big for her. She adjusted it as she sat in the chair across from Jesse’s desk.

“I’ve been doing a little off-hours

snooping,” Molly

said.

Jesse waited.

“Into the rape thing.”

“Candace Pennington,” Jesse said.

“Yes.”

“How you doing?” Jesse said.

“Well,” Molly said, “mostly

I’m just watching. I park outside in my own car, no uniform, and watch her come to school, and go home.

During lunch hour, I hang out in the cafeteria kitchen and watch. I know the food service lady down there, Anne Minnihan.”

“Find out anything?”

“Maybe,” Molly said. “There was

a moment this morning in the

cafeteria. Three boys sort of circled her and they stood and talked for maybe two minutes. They were all big and she was against the wall, and you could barely see her. One of them showed her something. The boys laughed. Then they moved away.”

“How did Candace react.”

“Scared.”

“You’re sure?”

“Yes. She was terrified, and … something else.”

“Something else?”

“Yes. I can’t quite say what. It was like whatever they’d shown

her was … horrifying.”

“Know the boys?” Jesse said.

“Not by name, yet,” Molly said.

“But I’d recognize all of

them.”

“Okay,” Jesse said. “We

don’t want to cause this kid any more pain than she’s already in. You need to ID these three boys without

them knowing it.”

“They were big, one of them was wearing a varsity jacket. I’ll

check the sports team photos in the lobby,” Molly said.

“Out of uniform,” Jesse said.

“Just a suburban mom waiting to

see the guidance counselor.”

“Hey,” Molly said.

“I’m not old enough to have kids in high school.”

“Vanity, vanity,” Jesse said.

“Cops can be vain,” Molly said.

“Sure,” Jesse said.

“You’re thinking especially if

they’re female, aren’t

you?”

Jesse leaned back in his chair and put his hands up.

He said, “I don’t have a sexist bone in my body, cutie

pie.”

“Anyway,” Molly said,

“I’ve lived in this town my whole life.

I’ll get them ID’d.”

“Okay, as long as you keep the kid in mind.”

“Candace?”

“Yes.”

“Hard to investigate a crime without anyone knowing it,” Molly

said. “For crissake, we can’t even talk to the victim.”

Jesse smiled. “Hard, we do at once,” he said. “Impossible takes

a little longer.”

“Oh God,” Molly said, “spare

me.”

Jesse grinned. “Just be careful of

Candace,” he

said.

“You’re very soft-hearted,

Jesse.”

“Sometimes,” he said.

12

Kenneth Eisley’s former wife had resurrected her maiden name,

which was Erickson. She worked as a corporate trainer at a company called Prometheus Plus, which was located in an office park in Woburn, and Jesse talked to her there, sitting in a chair made of silver tubing across from her desk. The desk too was made of silver tubing, with a glass top.

“Do you have any idea why someone might kill your former

husband?” Jesse said.

Christine Erickson laughed briefly and without amusement.

“Other than for being a jerk?” she said.

“Was he enough of a jerk to get himself shot?”

“Not that kind of jerk,” she said.

“He was a harmless

jerk.”

“Such as?” Jesse said.

“He thought it was important, I mean he actually thought it was

seriously important, who won the Super Bowl.”

“Everybody knows it’s the World Series that matters,” Jesse

said.

Christine looked blankly at Jesse for a moment. Jesse smiled.

Her demeanor was calm enough, Jesse noticed, but her movements seemed tight and angular.

“Oh,” she said.

“You’re kidding.”

“More or less,” Jesse said.

“What else was annoying about

him?”

Christine was wearing a dark maroon pantsuit with a white blouse

and short cordovan boots with pointy toes and heels a little too high to be sensible. She was slim and good-looking, with auburn hair and oval wire-rimmed glasses. Behind the glasses, her eyes were greenish.

“He believed the ads on television,” she said without

hesitation.

She’s talked about his faults before, Jesse thought.

“He thinks what matters is looking good, knowing the right

people, driving the right car, owning the right dog … Oh God,

what about Goldie?”

“He’s healthy,” Jesse said.

“Dog officer has

him.”

“What’s going to happen to him?”

“I was hoping you’d take him,”

Jesse said.

“Me. God no. I can’t. I work twelve hours a day.”

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

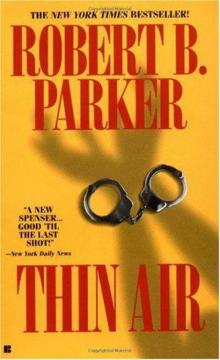

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22