- Home

- Robert B. Parker

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Page 3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Read online

Page 3

“God,” Allie said.

“Not much,” I said.

“You know, after I run off,” Allie said, “got taken up by a Mexican man, I think. He took me a ways and sold me to couple men who were half Comanche. They kept me awhile and sold me to Pig.”

I nodded. Virgil appeared to be asleep, though I doubted that he was.

“When I was in that place,” Allie said, “I started praying. I prayed that Virgil would come and find me. And you too, Everett.”

Allie didn’t want to hurt my feelings.

“Heard you praying back in the street,” I said.

“I was,” Allie said. “I believe it helped.”

“Didn’t hurt,” I said.

She nodded and went back to looking out the window. Virgil never stirred. The conductor came into our car, and the loud rattle of the train came in with him as he opened the door and passed from the next car to ours. When he came to us I handed him three tickets. He punched them and looked at the eight-gauge leaning against the corner of the seat by the window.

“What the hell’s that thing?” he said.

“Eight-gauge shotgun,” I said.

“You planning on hunting locomotives?” the conductor said.

“Only if one attacks me,” I said.

“Be a fool if it did,” he said, looking at the eight-gauge. “Where you folks headed.”

“Next town, I guess,” I said.

“That’d be Greavy,” he said. “You got business in Greavy.”

“Looking for work,” I said.

The conductor looked at Virgil and at me and at the eight-gauge. From the corner of his eye, he took a quick look at Allie in her pathetic dress and ratty Mexican sandals. But he didn’t look long.

“I guess you’re not cowboys,” he said.

“No,” I said. “We ain’t.”

“Well, good luck with it,” the conductor said.

“How long to Greavy?” I said.

“Maybe another hour or so,” the conductor said.

“Got a place there to buy ladies’ clothes?” I said.

“Sure, up-and-coming little town, Greavy. Got a good general store. Sells most everything.”

“Thanks,” I said.

He gave his cap bill a little tug and headed back down the train.

Nobody said anything for a while. Virgil remained motionless.

Then Allie turned from the window and said, “Thank you for asking about the clothes, Everett.”

I was pretty sure that was for Virgil. I was pretty sure all of her conversation had been for Virgil. She knew he wasn’t sleeping.

“Pleasure,” I said.

9

GREAVY WAS AN IMPROVEMENT over Placido. It was neat. Several of the buildings were painted. There were two restaurants, a bank, a big general store, and a big livery stable. We got Allie some clothes, ate some boiled beef and pinto beans at Chez Barcelona, and strolled on down to the marshal’s office. Allie hung back as we went in, and stood outside near the door. The marshal was a square-built man named Sheehan. He was as tall as Virgil and a little shorter than me. He wasn’t wearing a gun, though a Winchester lay on the desk beside him as we talked.

“Nope, sorry, boys,” he said. “Got six deputies already. More than the town needs except when they bring cattle in. You boys been marshaling before?”

“We have,” Virgil said.

“Whereabouts?” Sheehan said.

“All over,” Virgil said. “Most recent, I guess, we was in Appaloosa.”

“Appaloosa?” Sheehan said. “How recent?”

“Couple years now, ain’t it, Everett?”

“ ’Bout,” I said.

“You ain’t Virgil Cole?” Sheehan said.

“I am,” Virgil said.

“Jesus Christ,” Sheehan said.

“Wasn’t you up in Resolution last year?”

“I was, but I weren’t marshaling,” Virgil said. “This here’s Everett Hitch.”

“Sure thing,” Sheehan said. “I know who you are. You boys are famous.”

“Know any gun work around here?” I said.

“Maybe,” Sheehan said. “I don’t think he’s pressed, but the railroad just expanded service to Brimstone, up north a ways. They’re building new stock pens, more cattle coming in. And Dave Morrissey was saying last time I saw him he might need to add a couple gun hands.”

“Who’s Morrissey?” Virgil said.

“Val Verde County sheriff,” Sheehan said. “Up there filling in right now, ’cause he had a deputy quit on him.”

“Why’d the deputy quit?” Virgil said.

“Got married; wife insisted it was too dangerous.”

“How far up north,” Virgil said.

“ ’Bout two days’ ride,” Sheehan said. “Virgil Cole! By God! What I’m gonna do is I’m gonna wire Dave, tell him you’re coming. Tell him not to hire no one else.”

“ ’Preciate it,” Virgil said.

Allie came into the office almost tiptoeing.

“ ’Scuse me, Marshal,” she said. “I’m Allie French. I’m with these gentlemen, and I just bought some clothes. Do you suppose I could go into one of your cells and change?”

“Cells?”

“Long as you promise not to peek,” she said.

Sheehan looked at Virgil. Virgil nodded faintly.

“Sure thing, ma’am,” Sheehan said. He opened the door to the cell row.

“We got no guests at the moment,” he said. “Use any cell.”

Sheehan looked at us for a moment and decided not to ask anything.

“Whyn’t you boys wait here for the lady,” Sheehan said. “And I’ll go over and send Dave a telegram. Time you get there, he’ll be waiting for you.”

10

WE BOUGHT A BUCKBOARD and a mule for about what we’d sold one of the horses for. And with me driving, and Allie between us on the seat, we set out the next morning for Brimstone. Allie’s new clothes were an improvement. She had a ribbon in her hair. And she was wearing a little makeup. She was still kind of skinny. But she was looking better.

We were quiet. The buckboard was easy enough through the low grasslands, for a buckboard. There’s a reason it’s called a buckboard, and an easy ride ain’t it. The mule plodded along a sort of wagon rut west toward the Paiute River. It was sunny and hot. We could hear the soft coo of doves, and occasionally we kicked up a flutter of them as we rode by. We passed cattle. Mostly shorthorns, but still now and then a longhorn bull.

Virgil was looking at the landscape.

“Wolves,” he said.

The mule must have caught scent of them. He tossed his head and shied and made a short snorting sound. I didn’t see them yet. Then I did, three gray shapes trotting in line, heading east, appearing and disappearing in the high grass.

“Following that cattle herd,” I said.

“Likely,” Virgil said.

“Are you going to shoot them?” Allie said.

“No reason,” Virgil said.

“But the cattle…” Allie said.

“Not my cattle,” Virgil said.

“But the poor cows,” Allie said.

“What you think them cows are for, Allie? Wolves eat ’em. People eat ’em. Don’t seem to me make much difference to the cow.”

Allie watched them until they were gone, and the mule settled back into his walk.

“How’d you see them so quick, Virgil,” Allie said.

“Eyesight’s good,” he said.

“But it’s more than that, isn’t it?” Allie said. “You always see everything.”

Virgil didn’t answer. We rode in silence for a while.

Then Allie said, “You know what I’d like to do again?”

Virgil didn’t say anything.

So I said, “What’s that, Allie.”

“I’d like to be Allie again.”

“Be nice,” I said.

“It would,” Allie said.

Virgil was looking at the landsc

ape again.

“Virgil isn’t very talkative,” Allie said. “Is he, Everett.”

“Don’t seem so,” I said.

“Used to be a talker,” Allie said.

I nodded.

“How come you don’t talk to us, Virgil?” Allie said.

“Got nothing to say,” Virgil answered.

“When we were together in Appaloosa,” Allie said, “you used to talk a lot about nothing.”

“Lotta things happened since Appaloosa,” Virgil said.

“You thinking about all those things, Virgil?” Allie said.

“Yep.”

“Wasn’t easy on me, you know?” Allie said.

“I know.”

“You gonna stop thinking about all that, one of these days?” Allie said.

“Might,” Virgil said.

Nobody said anything else. I looked over at Allie once and saw that her lips were moving. Appeared she was praying again. Other than that, we bumped along in silence until we reached the Paiute River, where we made camp and slept under the buckboard.

11

WE HEADED NORTH ALONG the Paiute at sunrise, and by the middle of the afternoon we were in a hotel in Brimstone, Allie and Virgil in one room, me next door.

“Heard you was out of the law business,” Dave Morrissey said when we went to see him.

“Was,” Virgil said.

“What changed your mind?” Morrissey said.

Virgil was silent for a moment.

“Well, some things bothered me,” Virgil said. “But Everett and I talked some, and now they don’t bother me so much.”

I was startled. First time he’d ever admitted that I had any influence on him.

“Anything else?” Morrissey said.

Virgil grinned.

“Need the money,” he said.

Morrissey nodded.

“Ain’t quite commensurate with the risk,” he said. “But only a fool would do it for free.”

“How ’bout you, Hitch?” Morrissey said.

He looked like he might have been a cowboy once, sort of bowlegged and smallish. He had a big drooping mustache, and wore a long duster.

“Well,” I said, “I done law and not law for a long time. Don’t make a lot of difference to me. I’m not too scared, and I’m decent with the eight-gauge.”

“That’s what that thing is,” Morrissey said. “Thought it might be a cannon.”

“Two barrels,” I said.

Morrissey grinned.

“God’s truth,” he said. “I heard about you boys, and when Sheehan telegrammed me I was interested. I’m told you’ll stand, and your word is good.”

“It is,” Virgil said.

“And I hire you, you won’t sell me out for a higher offer.”

“We don’t promise to work for you forever,” Virgil said. “But we won’t work against you, ’less you force it.”

“Fair enough,” Morrissey said. “What I told Sheehan was true, we’re booming. Cattle mostly. Railroad’s expanding, bigger herds coming in. I come down from Del Rio every once in a while, and a Ranger comes by every month or so. But right now there ain’t no permanent law here, and the place is growing like a damn weed.”

“Town grows too fast,” Virgil said, “leaves an empty space; people fight to fill it.”

“You’ve worked a lot of towns,” Morrissey said.

“We have,” Virgil said.

“The situation in this one is a little peculiar,” Morrissey said. “We have a fella named Pike. I don’t even know his first name. Everyone calls him Pike… Hell, maybe Pike is his first name.”

Virgil shrugged.

“Anyway,” Morrissey said, “he showed up here a few years ago with the remains of a gang that the Pinkertons chased into exhaustion.”

“They’ll do that,” I said.

“Sometimes,” Morrissey said. “He had a few of his boys with him and some money they probably stole from a railroad, and they bought a saloon at the north end of town. Never broke no law here. And they run a first-class operation. Booze is good, games are honest, girls are clean. They police themselves. No trouble. We’ve never even had to go up there since they been in town.”

“Model citizens,” I said.

“And then, ’bout a year ago, here come Brother Percival.”

“Percival,” Virgil murmured.

“What he calls himself,” Morrissey said. “Brother Percival.”

“Preacher?” I said.

“Yep,” Morrissey said. “Come to town with a tent show, preaching against sin like he was the first man to discover it. Nobody paid him much attention for a time. But he kept collecting people to his whatever it is, and then he built himself a church, brought in a damned organ from Kansas City. And him and some of the people come with him when he arrived, they decide to make a target of the biggest and best saloon in town.”

“Pike’s,” Virgil said.

“What’s Brother Percival want?” I said.

“Damned if I know. Maybe he is acting on behalf of the Kingdom of Heaven. Maybe he wants to take over Texas.”

“And Pike?” I said.

Morrissey smiled a little.

“He wants to take over Texas,” Morrissey said.

“Potential there for conflict,” Virgil said.

Morrissey nodded.

“You want the job?” he said.

“Sure,” Virgil said.

12

“COMMENSURATE?” Virgil said outside Morrissey’s office.

“Sort of like equal to,” I said.

“Might as well go right at ’em,” Virgil said. “See what we got.”

“Which one first?” I said.

“Start with Pike,” Virgil said.

“More our type,” I said.

“Ain’t so sure we got a type,” Virgil said.

Brimstone was about seven blocks wide and ten blocks long in a green bend of the Paiute River, which made it cooler than this part of Texas usually was. Pike’s Palace was halfway down Arrow Street, on the west corner of Fifth Street, putting it about in the center of the town. All around it, the town was busting out of its skin. Freight and lumber were being hauled through town. Buildings were going up, saloons and eating places were crowded, and there were two general stores, a bowling alley, two millinery shops, and two hotels already and a third one being built. The air was full of sounds: wagons creaking, men swearing, mules, oxen, carpentry, and black- smithing. At the north end of Arrow Street was a big town hall, almost finished. At the south end was a church with an imposing spire. There were boardwalks lining every street, and most of the buildings had roofed out over the boardwalk in front of them, so you could shelter from the sun in good weather and the rain in bad.

The saloon had a corner entrance and heavy oak doors, which were opened back in good weather and let you into a vestibule with swinging doors ornamented by stained-glass windows. Through the swinging doors was the saloon.

Wearing our new deputy stars, we stopped inside the doorway and looked around.

“Pike done himself proud,” Virgil said.

“Did,” I said.

Along the length of one wall, which seemed from inside to run nearly the whole block along Fifth Street, was an elaborate mahogany bar with a black mirrored wall behind it and bottles stacked in decorative pyramids. Along the other wall was a row of gaming tables, and in the open space between were tables and matching chairs. There was an ornate chandelier shedding light on the windowless room, and at the back a set of stairs that led to a second floor. The wide plank floors were polished. The bar top gleamed. The saloon whores were neat. And the glassware appeared clean. Four bartenders worked the bar, which was busy in the late afternoon, and a thin, dark, sharp-faced guy with a shotgun sat in the lookout chair near the far end of it. Virgil walked down the length of the bar to him.

“J.D.,” he said.

The lookout examined Virgil.

Then he said, “Wickenburg.”

“Ye

p.”

“Virgil Cole,” J.D. said.

“Yep.”

“You posted us out of town,” J.D. said.

“You was with Basgall,” Virgil said.

“Moved on,” J.D. said.

“And Basgall?”

“Got shot by two Texas Rangers in El Paso.”

“You with Pike now?” Virgil said.

“I work here,” J.D. said. “You?”

“Me and Hitch here signed on with the sheriff,” Virgil said.

“Seen the badges,” J.D. said.

“Like to talk with Pike,” Virgil said.

J.D. nodded.

“Spec,” he said to one of the bartenders, “go tell Pike new deputy wants to see him.”

“Name’s Virgil Cole,” Virgil said.

Spec nodded and walked to a door under the back stairs. In a moment he returned, and behind him was a big man with very little hair and a short beard.

“Virgil Cole,” he said, and put his hand out.

Virgil didn’t take it.

“This here’s Everett Hitch,” Virgil said.

Pike didn’t seem to mind not shaking hands.

“Good to meet you, Everett,” he said. “You fellas care for a drink?”

“Beer’d be good,” Virgil said.

Pike nodded at the bartender and led us to an empty table.

“Bartender says you and J.D. know each other,” Pike said.

“Wickenburg,” Virgil said.

The bartender arrived with three mugs of beer and placed them carefully before us.

“Thank you, Spec,” Pike said.

He raised his mug toward us. We drank.

“J.D. is a pretty good gun hand,” Pike said.

“Was,” Virgil said.

“Still is,” Pike said.

“Likely so,” Virgil said. “I just ain’t seen him lately.”

Pike was deceptive. When you first saw him you thought he was fat. But when he moved he seemed light on his feet, and quick. And when you sat with him, up close, and could look at him you realized that he was big and barrel-shaped, but not much of it was fat. I looked around the saloon.

“Done yourself proud here, Mr. Pike,” I said.

“Aw, just Pike. Nobody calls me Mister.”

“Well, you got a nice place here,” I said.

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

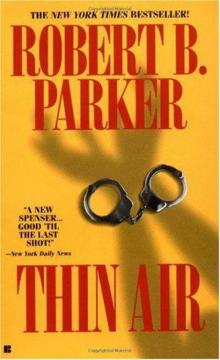

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22