- Home

- Robert B. Parker

Hundred-Dollar Baby Page 6

Hundred-Dollar Baby Read online

Page 6

“Nothing we can’t fix,” I said. “Whatever the truth is, it’s nothing we can’t fix.”

She turned her face into my chest and cried some more. I patted her shoulder. The crying slowed. She wriggled against me a little and raised her head and looked at me. I smiled at her. Suddenly she leaned in against me and kissed me with her mouth open and tried to put her tongue in my mouth. I was horrified. It was like getting French-kissed by your daughter. I turned my head.

“April,” I said.

She had squirmed herself on top of me as I leaned back against the corner of the couch, so that she pressed full-length against me.

“You’ve never touched me,” she said. “Not since you met me. You’ve never touched me.”

“You were pretty young,” I said.

“And now I’m not,” she said.

Her face was so close to mine that her lips brushed my face when she spoke.

“Too late,” I said. “It would be like incest.”

She was moving her body against me as she lay on me.

“Wouldn’t you like to fuck me?” she said. “I’m good-looking and I’m really good at it.”

“No,” I said.

“Just once? Fuck me just once? I really know how.”

I sat somewhat forcibly up and got my arms under her and stood up with her, and turned and set her back on the couch. She was still, flopped back as if she were exhausted, looking at me with her eyes half closed.

“You know you want to,” she said. “Men always want to.”

I looked at her for a moment without speaking.

Then I said, “Thanks for the offer,” and turned and left the apartment.

18

Susan was back from Albany. She smiled when I finished my recitation.

“I guess April didn’t want to talk about the case,” Susan said.

“You think?”

Susan nodded.

“I do,” she said. “And I have a Ph.D. from Harvard.”

We had ordered dinner in Excelsior, at a table by the window, looking out over the Public Garden, and we were having cocktails while we waited.

“It’s all she knows how to do,” I said.

“And quite well,” Susan said, “if you were reporting accurately.”

“She says she does it quite well,” I said.

“It’s not terribly difficult to do well,” Susan said.

“May I say you’ve mastered it,” I said.

“Must I remind you again of the Harvard Ph.D.?” she said.

“Wow,” I said, “they got courses in everything.”

Susan took a small sip of her Cosmopolitan.

“It’s a refrain I hear often,” Susan said. “From patients. Women who are sexually active and have a limited skill set often brag about how good they are at sex.”

“It’s not really a matter of technique,” I said.

“Fortunately for you,” Susan said.

“Hey,” I said.

She smiled.

“It has much to do,” Susan said, “with whether you are happy in the task.”

“So maybe she protesteth too much?”

“I’m sure she knows all there is to know,” Susan said. “But most adult women do.”

“Not all of them.”

“There are a thousand things that can inhibit someone’s sexuality. But lack of skill is not a common problem.”

“Really,” I said. “You didn’t learn any of this up in Albany, did you?”

She grinned at me. The big, wide grin, full of things hinted but not exactly said.

“I haven’t cheated on you in ages,” Susan said.

“Good to know,” I said.

“But, I was a grown woman when I met you,” Susan said. “Remember? Married and divorced. I had already learned a lot of things.”

I nodded.

“And there was that little business out west,” she said.

“That was then,” I said. “This is now.”

She looked steadily at me with no banter. My hand was on the table. She put her hand on top of it.

“Yes,” she said. “It is.”

We were silent. I drank some scotch. She drank some Cosmopolitan.

“I’m running around this thing like a headless chicken,” I said.

“My guess would be,” Susan said, “that whatever answers you’re likely to get will come out of April.”

“She denies all,” I said.

“She has a past,” Susan said. “Maybe that will tell you something.”

I nodded slowly, thinking about it.

“What got her in trouble last time?” Susan said.

“Looking for love in all the wrong places.”

“And the time before that,” Susan said. “When you first met her?”

“Looking for love in all the wrong places,” I said.

“Without some sort of major intervention,” Susan said, “people don’t change much.”

“Cherchez l’homme,” I said.

Susan nodded. “Maybe,” she said.

“You Ivy Leaguers are a smart lot, aren’t you?”

Susan nodded vigorously.

“Wildly oversexed, too,” she said.

“Not all of you,” I said.

“One’s enough,” she said.

“Yes,” I said. “It is.”

I raised my glass toward her. She picked up hers. We clinked.

“Fight fiercely, Harvard,” I said.

19

In New York I stayed at the Carlyle hotel. I could have stayed at a Days Inn on the West Side for considerably less. But I would have gotten considerably less, and I’d had a good year. I liked the Carlyle.

Thus, on a bright, windy day in New York, with the temperature not bad in the upper thirties, I sat with Patricia Utley in the Gallery on the Madison Avenue side of the hotel and had tea. It was elegant with velvet and dark wood. Faintly from the Café I could hear piano music, somebody rehearsing for the evening. Barbara Carroll? Betty Buckley? I felt like I was in Gershwin’s New York. I was more sophisticated than Paris Hilton.

“A professional thug,” I said. “And a whorehouse madam having tea at the Carlyle. Is this a great country or what?”

“We look good,” Patricia Utley said. “It covers a multitude.”

We did look good. I looked like I always do: insouciant, roguish, and quite similar to Cary Grant, if Cary had had his nose broken more often. Patricia Utley wore a blue pin-striped pantsuit and a white shirt with a long collar. Her short hair had blond highlights, just like April’s. Her makeup was discreet. She looked in shape. And the hints of aging at the corners of her face seemed to add some sort of prestige to her appearance.

We ordered the full tea. I like everything about tea, except tea. But I tried to stay with the spirit of it all.

“I’ve been chasing my tail,” I said, “since I started with April.”

Patricia Utley sipped some tea and put her cup down.

“And you wish my help?” she said.

“I do.”

We both paused to examine our tea sandwich options.

“Let me tell you what I know, and what I think,” I said.

“Please.”

She listened quietly, sipping her tea, nibbling a cucumber sandwich. She seemed interested. She didn’t interrupt.

When I was finished, she said, “You think there’s a lover or ex-lover somewhere in the picture?”

“I think I should find out if there is.”

“What do you need from me?” she said.

“Information.”

“Information is problematic,” Patricia Utley said. “I am in a business which deeply values discretion.”

“Me too,” I said.

She smiled.

“So we will be discreet with one another,” she said.

“I need to have some names, someplace to start,” I said. “Can you give me a list of her clients in the last year, say, when she was with you in New York?”

>

“Why would you think that I would have such a list.”

“You’re a woman of the twenty-first century,” I said. “You have a database of clients in your computer, or my name is not George Clooney.”

“You’re bigger than George Clooney,” Patricia Utley said.

“Yeah, but otherwise…” I said.

“An easy mistake to make,” she said.

“I won’t compromise you,” I said. “But I need to see if she had a more than, ah, professional encounter with any of them.”

She had some more tea, and a scone, while she thought about it.

“I have learned not to trust anyone,” she said.

I waited.

“But oddly,” she said, “I trust you.”

I smiled my self-effacing smile, the one where I cock my head to the side a little.

“Good choice,” I said.

“You won’t compromise me,” she said.

“Of course I won’t.”

“Of course you won’t.”

“So I get the list?” I said.

“I’ll have it delivered to you tomorrow,” she said. “Here.”

“Oh good,” I said. “I’ll pay for tea.”

20

The list of April’s regular partners was a good one. There were about fifteen names on it; each was annotated with the dates of contact, how they paid, how to reach them, what their preferences were. I was pleased to see that their preferences were within normal parameters.

The direct approach might not be productive: Hi, I’m a private detective from Boston. I’d like to talk with you about your long-term relationship with a professional prostitute. I decided to consult a New York professional. And I knew who to call.

I met Detective Second Grade Eugene Corsetti for lunch at a Viand coffee shop on Madison Avenue, a couple of blocks uptown from the hotel. We sat in a tight booth on the left wall. It was tight for me, and Corsetti was as big as I was but more latitudinal. He was built like a bowling ball. But not as soft. I ordered coffee and a tongue sandwich on light rye. Corsetti had corned beef.

“How can you eat tongue,” Corsetti said.

“You know how intrepid I am.”

“Oh, yeah, I forgot that for a minute.”

“You make first yet?” I said.

“Detective First Grade?” Corsetti said. “You got a better chance of making it than I have.”

“And I’m not even a cop anymore,” I said.

“Exactly,” Corsetti said.

The coffee came. Corsetti put about six spoonfuls of sugar in his and stirred noisily.

“Is that because you annoy a lot of people?” I said.

“Yeah, sure,” Corsetti said. “Always have. It’s a gift.”

The sandwiches came, each with half a sour pickle and a side of coleslaw. Corsetti stared at my sandwich.

“You’re gonna eat that?” he said.

I nodded happily.

“Want a bite?” I said.

“Uck!” Corsetti said.

“You remember first time I met you?” I said.

Corsetti had a mouthful of sandwich. He nodded as he chewed.

“You were looking for a missing hooker,” he said after he had swallowed and patted his mouth with his napkin.

“April Kyle,” I said.

“Yeah,” Corsetti said. “And somebody involved in it got killed a few blocks east of here, I think.”

I nodded.

“And I caught the squeal,” Corsetti said. “And there you were.”

“And a few years later, at Rockefeller Center?”

“Heaven,” Corsetti said. “I got a lot of face time on the tube out of that one. Whatever happened to the guy you had hold of.”

“We arranged something,” I said.

“Lot of that going around,” Corsetti said. “Whaddya want now?”

“Renew acquaintances?” I said.

“Yeah, sure, want to hold hands and sing ‘Kum By fucking Ya’?”

“I’m working on April Kyle again,” I said.

“The same whore? She run off again?”

“No,” I said. “She’s in trouble.”

“And her a lovely prostitute,” Corsetti said. “How could that be?”

“I have a list of names; I was wondering if you could run them. See if any of them are in the system anyplace.”

“Where’d you get the list?”

“They’re former clients of April Kyle.”

“So they’ll be thrilled to have their names run,” Corsetti said.

“We hope they won’t know,” I said.

“Who’s we?”

“Me and the madam who gave me the list,” I said.

“I ain’t vice,” Corsetti said. “I don’t give a fuck about whores. What are you looking for?”

Corsetti was through eating. All I had left on my plate was half a pickle. I ate it.

“There’s some sort of cherry pie over there on the counter,” I said. “Under the glass dome.”

“Yeah,” Corsetti said. “I spotted it when I come in.”

“I’m not going to have any,” I said.

“No, me either,” Corsetti said. “You gonna tell me what you’re doing?”

“Okay,” I said, and told him.

As I was telling him the waiter cleared our plates. I paused.

“Anything else?” the waiter said.

“More coffee,” Corsetti said. “And two pieces of the cherry pie. Some cheese.”

“You got it,” the waiter said and walked away.

Corsetti and I poisoned ourselves with pie and cheese, while I finished explaining. When I was done, Corsetti put out his hand.

“Gimme the list,” he said. “I’ll get back to you.”

21

I spun my wheels for a couple of days until I finally met Corsetti again, this time in Grand Central Station.

“Why here?” I said as we sat together on a bench in the vast vaulted waiting room. Each of us had coffee in a plastic cup.

“I like it here,” Corsetti said. “I come here when I get a chance.”

The light was streaming in from the high windows. The room was busy with people. It was New York from another time, lingering into the twenty-first century. Corsetti handed me a big manila envelope.

“Here’s your list back,” Corsetti said. “I made some notes. You can go over it later.”

“Anything good?” I said

“I only got one guy,” Corsetti said. “Lionel Farnsworth.”

“What’d he do?” I said.

“LF Real Estate Consortium,” Corsetti said. “Bought a bunch of slab two-bedroom ranches in North Jersey. Fore-closure junk. And resold them for a lot more to yuppies in Manhattan with the promise of high rental income and positive cash flow. He took a packaging fee on the deal and arranged the financing, for which he got a finder’s fee from the bank.”

“And?”

“Some of the property was condemned. Most of the houses needed rehab. Residents couldn’t pay the rent. And the yuppies were left holding a bagful of garbage.”

“And one of them got a lawyer,” I said.

“They got together and got one,” Corsetti said. “And he went to the Manhattan DA. And Manhattan talked to our cousins in Jersey.”

“And?”

“Because the crime was interstate, Jersey and New York, the Feds got involved. There were some really swell turf battles, but eventually Lionel did two years in Allenwood, for some sort of interstate conspiracy to defraud.”

“White Deer, Pennsylvania,” I said.

“Sounds like a vacation spot,” Corsetti said.

“Minimum security pretty much is,” I said. “Got dates?”

“It’s all in there,” Corsetti said. “I’m just giving you highlights.”

“Nobody else in the system?” I said.

“Nope.”

A bum came shambling past us.

“You gen’lemen got some change?” he said.

Corsetti reached for his wallet. When he did, his coat fell open and the bum could see the gun and the shield clipped onto Corsetti’s belt next to it. The bum backed away.

“Never mind,” he said. “I didn’ mean nothing.”

Corsetti took out his wallet.

“Step over here,” Corsetti said.

“Yessir.”

The bum shuffled back. He didn’t look at either of us. He looked at the floor. His shoulders hunched a little as if maybe Corsetti was going to hit him.

“I got no change,” Corsetti said.

He handed the bum a ten-dollar bill. The bum took it and stared at it. He still didn’t look at Corsetti, or me.

“Beat it,” Corsetti said.

“Yessir,” the bum said. “God bless.”

He backed away with the bill in his hand, still looking at it, then turned and walked away across the waiting room under the high arched roof toward 42nd Street.

“Fucking stumblebums,” Corsetti said. “The uniform guys come through couple times a day, sweep ’em out, but they’re right back in here a half-hour later.”

“Especially in the winter,” I said. “Is ‘stumblebum’ the acceptable term for our indigent brothers and sisters?”

“Sometimes I like ‘vagrants,’” Corsetti said. “Depends on how much style they got.”

“Think the money will help him?” I said.

“Nope.”

“Think he’ll spend it on booze?”

“Yep.”

“So why’d you give it to him?” I said.

Corsetti swallowed the last of his coffee and grinned at me.

“Felt like it,” he said.

22

I spent an hour looking at Patricia Utley’s list as annotated by Eugene Corsetti. Corsetti had thoughtfully located all fifteen guys by address and phone number for me. And he had included copies of Farnsworth’s mug shots from when they’d made the first fraud arrest in 1998. Other than that, Corsetti didn’t add much to what he had told me in the waiting room. I wanted to take a look at Lionel Farnsworth, so I walked across the park to where he lived, about opposite the Carlyle, in one of those impressive buildings that front Central Park West.

I wasn’t sure what I thought I’d learn. The mug shots were old enough so that he might have changed, certainly. And people don’t always look just like themselves when they’re being booked. He would look different in the flesh. And I had some half-articulated sense that if he looked wrong for the part, I’d know it. Besides, I couldn’t think of anything else to do.

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

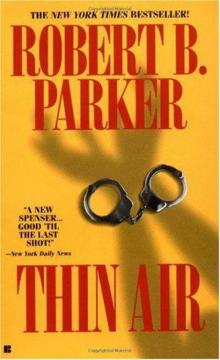

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22