- Home

- Robert B. Parker

A Catskill Eagle Page 7

A Catskill Eagle Read online

Page 7

“Figure they got the Bronco out of there yet?” Hawk said.

“Somebody probably popped the ignition,” I said.

“I don’t know,” Hawk said. “Got to be city to know about popping ignitions. They don’t look city to me.”

We were heading for 101 again. I was getting used to the trip. Hawk kept the car at fifty-five and we went sedately through the quiet California night, moving briskly, going no place special.

“Got to look at this lodge,” I said.

“They know we coming,” Hawk said.

“Still got to look,” I said.

“They’ll have something set up for us,” Hawk said.

“And they’ll have taken Susan somewhere else,” I said.

“Still got to look,” Hawk said.

CHAPTER 14

“IT BOTHERING YOU THAT WE DON’T KNOW where this lodge is,” Hawk said, slouched down in the Volvo.

We were in the parking lot of the Fisherman’s Wharf Holiday Inn, parked in a slot near the building where a passing cop wouldn’t wonder about us at 3:00 A.M.

“We’ll ask Dr. Hilliard,” I said.

“Susan’s shrink? How’s she gonna know?”

“Maybe she won’t. But people talk about things with shrinks, and shrinks are used to remembering.”

The seat backs in the Volvo reclined back and we lay in the dark car nearly prone.

“Been good,” Hawk said, “we collected some firearms while at Costigan’s.”

“I know,” I said. “Things just got rolling downhill.”

“Things been doin‘ that since we got here,” Hawk said.

“Readiness is all,” I said.

It was very quiet. Occasionally I could hear the sound of a truck easing up through the gears along the Embarcadero. It was a little chilly in the darkness but I didn’t want to turn on the heater. An idling car might attract a cop.

“We piling up some pretty good-looking list of charges,” Hawk said. “We got B and E and assault for sure at Costigan’s, to go along with murder one and felonious escape and assault on police officers.”

“I wonder if they can make us on kidnapping?” I said.

“Holding Costigan and the missus?” Hawk said. “If they do, it a chicken shit charge.

“Of course we have two counts of murder and one count of armed robbery for Leo and his driver.”

“If they make us,” Hawk said.

“If they try hard,” I said.

“Figure San Francisco cops won’t get real hysterical somebody dusted Leo.”

A light went on in one of the guest rooms in the hotel. It stayed on maybe two minutes then went off again. Susan wouldn’t be there when we found the lodge. The Costigans weren’t that stupid. But we had nowhere else that made any more sense to look. So we’d find it. And the Costigans would be waiting for us and maybe when that worked out there’d be more momentum rolling downhill and maybe something would come out of it. I thought of her face laughing in the picture beside Russell: I thought of Hawk’s description of her with the frozen half smile and the tears in her eyes. Things are awful, but I love you. I thought of Leo when I shot him. Had to do that. No other way. The whores would have suffered for it and it wasn’t their fault. A night watchman walked through the parking lot, his heels loud as he came. Hawk and I stayed slouched and motionless as he passed. It wasn’t the whores’ fault. But they didn’t have to be whores. Maybe they did. I didn’t like shooting Leo. But I had to find Susan.

“How the Christ did we end up here,” I said.

“I the victim of sociological forces,” Hawk said.

“You’re a goddamned leg breaker because of racism?” I said.

“No, I a leg breaker ‘cause the hours are short and the pay is good. I end up here ’cause I hanging around with a middle-aged honkie thug. You what your momma wanted?”

“Don’t remember my mother,” I said. “I was raised by my father and my two uncles. My mother’s brothers.”

“They stay with your father?”

“Yeah. They had a carpentry business. How my father met my mother.”

“She split or she die?” Hawk said.

“Died.”

The security guard moved back up the next line of cars. His footfall muted slightly as he moved away.

“We locate this lodge,” Hawk said. “Maybe we better like get outfitted, you know. Bullets, jackets, a belt for you, that kind of thing.”

“First we find out where it is,” I said and shifted in my seat. I’d never slept on my back and wasn’t getting any better at it.

At five thirty the sun was up. At six thirty we found a place open that sold us coffee and English muffins, and at seven thirty I called Dr. Hilliard from a pay phone on the corner of Beach Street and Taylor. Her service answered and I asked that she call me as soon as she could.

“It’s about Susan Silverman,” I said. “And it’s life and death. Tell Dr. Hilliard that.” I gave the number of the pay phone and hung up and stayed there. Two people stopped and looked at the phone and each time I picked it up and listened to the dial tone until they moved on. At seven fifty-five the phone rang.

I picked it up and said, “Hello.”

“This is Dr. Hilliard.”

I said, “My name is Spenser. Probably Susan Silverman has mentioned me.”

“I know the name.”

“She’s in trouble. My kind of trouble, not yours. I need to talk with you.”

“What specifically is your kind of trouble?”

“Russell Costigan is holding her against her will,” I said.

“Perhaps that grew out of my kind of trouble,” she said.

“Yes,” I said. “But she needs my kind of help now, so she can get your kind of help soon.”

“Be at my office at eight-fifty,” Dr. Hilliard said. “Since you knew my phone number I assume you know my address.”

“Yes,” I said. “I’ll be there. Have you seen me on television?”

“Yes.”

“Are you going to call the cops when I hang up?”

“No.”

CHAPTER 15

HAWK WAITED OUTSIDE AND I WENT IN. DR. Hilliard’s office was in a big pastel mauve Victorian house on Jones Street near Filbert. There was a walkway made of two-by-eights that led around to the back door and a sign that said RING BELL AND ENTER. I did both. I was in a small beige waiting room with two chairs and a table between, with a clean ashtray on it. The chairs and table were Danish modern. The ashtray was several-colored mosaic that looked like it might have been someone’s Cub Scout project. There was a pole coatrack with its top spring slightly askew, and a pole lamp with one of its three bulbs burned out. On the table were piles of New Yorker magazines, some Atlantic Monthlys, some Scientific Americans. And, on the opposite wall, a pile of intellectual magazines for children. No Marvel Comics. No Spiderman. No National Enquirer. Maybe people with plebian tastes didn’t get crazy. Or didn’t get cured. In the corner of the room opposite the entry door was a wide staircase that went to a landing six steps up then turned out of sight. The stairway and the waiting room were carpeted in quiet gray and a white sound machine shushed on the floor in the other corner near the radiator. I sat in the chair near the radiator. In two minutes a young woman in black tweed slacks and a frilly white blouse came down the stairs and out the door without looking at me. There was the sound of movement upstairs, a door opening and closing, then another silent minute and then a woman appeared at the landing and said, “Mr. Spenser?”

I said, “Yes.”

She said, “Come on.”

And I went up the stairs. Dr. Hilliard was standing in an open door at the end of a short hall at the top. I walked past her into the office. She closed the door behind me; then another. Secure. No secrets will escape. Doctor I can’t stand my mother. Doctor I never achieve climax. Doctor I’m afraid. The double doors keep it all in. So you can let it out. Doctor I’m afraid I’m gay. Doctor I can’t stand my husband. The truth busi

ness. Behind the double doors. Doctor I’m afraid.

I said, “No cops.”

She said, “No cops.”

I sat in the chair by her desk. Behind me was a couch. For crissake there actually was a couch. Beyond the desk was a tank in which tropical fish drifted. There were diplomas on the wall and a bookcase filled with medical books, next to the double door. Dr. Hilliard sat down. She was maybe fifty-five or sixty. White hair in a French twist, good makeup well applied. A look of outdoor color to her skin. She wore a black skirt and a doublebreasted black jacket with a black-and-silverstriped silk shirt, open at the neck, the collar spilling out over her lapels. There was a heavy antique gold chain around her neck from which a diamond hung. Her earrings were old gold too, with diamond chips. On her left hand was a white gold wedding band.

“What do you know about me?” I said.

“You are a detective. You and Susan have been lovers. You have suffered, what, an attenuation of your relationship recently, but that bond between you remains truly impressive. If I am to believe Susan you are, though flawed, inherently good.”

The weight of Dr. Hilliard’s intelligence was palpable. She reminded me a little of Rachel Wallace. In fact she reminded me some of Susan. There was in her the force and richness that Susan had.

“I bet you made up the part about ‘flawed,’” I said.

Dr. Hilliard smiled. “The reality I try to deal with in here is hard enough,” she said. “I don’t have to make anything up.”

So much for light badinage.

“Here’s what I know,” I said. “A year or so ago Susan went to Washington to intern. She met Russell Costigan and they began an affair. When she got her Ph.D. she moved out here and set up in Mill River, working at an outreach clinic at Costigan Hospital there. We stayed in touch and when she found she could neither give me up nor come back to me she began to seek your help. About two weeks ago she called a mutual friend, Hawk.”

“The black man on the news with you,” Dr. Hilliard said.

“Yes. And she said she needed help and she felt she couldn’t ask me and would Hawk come out. He did. He got into a scrape with Russell Costigan and the Mill River cops. A man was killed, Hawk was arrested. Susan sent me a letter. The letter said, `I have no time. Hawk is in jail in Mill River, California. You must get him out. I need help too. Hawk will explain. Things are awful, but I love you.‘ I came out and busted him out of jail and we went up to Jerry Costigan’s house looking for Susan and didn’t find her but heard she was at `the lodge.’ And we left and came here and I want to know, among other things, where `the lodge‘ is.”

Dr. Hilliard smiled. “‘Hawk will explain,’” she said. “She never doubted that you’d come or that you’d rescue him.”

“Do you know where this lodge is? Has Susan ever spoken of it?”

Dr. Hilliard sat perfectly still, her hands folded in her lap. “You clearly can’t go to the police with this. Though perhaps I might?”

“Which police,” I said. “What jurisdiction. Logically it’s Mill River. That’s where she lived. But they belong to the Costigans. They were part of the setup for Hawk.”

She pushed her lower lip out slightly and drew it back in. Her eyes were steady on my face.

“The lodge is in the Cascade Mountains, outside of Tacoma, Washington. Crystal Mountain. The police there, informed that there was a possible kidnapping, might be effective.”

I shook my head. “We don’t know whether Costigan owns them too,” I said. “He’s an owner. He would be inclined to influence his neighborhood. Wherever his neighborhood was.”

Dr. Hilliard nodded.

“Besides,” I said, “Susan won’t be there. They know we will go there.”

“Then why go?” Dr. Hilliard said.

“It’s a place to start.”

Dr. Hilliard nodded again. We were quiet. The fish drifted in their tank.

“You’ve not asked me about Susan,” Dr. Hilliard said. “Most people would have.”

“What happens in here is hers,” I said.

“And when you find her. Then what?”

“Then she will be free again to come here and work with you until she can make the choices she wishes to make.”

“And if you are not that choice?”

“I think I will be. But I can’t control that. What I can do is see that she’s free to choose.”

“Control has been an issue,” Dr. Hilliard said. It was neither a question nor a statement, simply a neutral utterance.

“I think it has been,” I said. “I think I probably tried too much to control her. I’m trying to cut back on that.”

“Have you been in therapy, Mr. Spenser?”

“No, but I think a lot.”

“Yes,” Dr. Hilliard said..

The fish drifted. Dr. Hilliard was motionless. I didn’t want to leave. Susan had come here every week, maybe more than once a week. She had sat in this chair, or the couch? No. She would have sat in the chair, not lain on the couch. Before me was a woman who knew her. Knew her perhaps in ways that I didn’t. Perhaps in ways that no one did. Knew about her relationship with me. With Russell. I was sitting with my hands clasped behind my head. Unbidden the biceps tightened in my upper arms. I saw Dr. Hilliard notice that.

“I was thinking of Susan with Russell Costigan,” I said.

Dr. Hilliard nodded.

“Susan,” she said, “grew up in a family of people, who, out of their own phobic needs, treated her as an item, a thing useful for making them feel good, or important, or adult. She never learned to value herself as a person, only as someone else’s person. As she matured and learned, she became more aware of this. It was the basis of her first marriage. She was, after all, training to be a psychologist, and her work had been in that line for years. At the time that this insight began to take shape, your need for her became more intense, and it manifested itself to her as control. She had to get away.”

“And Russell rescued her,” I said.

“He rescued her from you. Now you will rescue her from him,” Dr. Hilliard said. “I share your view that it must be done. Her situation is hopeless if she is not free. But it would be better were she able to rescue herself from him.”

Dr. Hilliard paused and looked straight at me. The pause lengthened. Finally she said, “I am torn. The confidentiality of Susan’s therapy is imperatively important. But in order to save her spirit, we must first save her physical self.”

I didn’t say anything. I knew what I said wouldn’t be what decided Dr. Hilliard.

“It is important for you to remember that she fears dependency, despite, in fact because of, its attractiveness to her. Being rescued will do nothing to dispel those fears. It will present you as more complete, more dangerous to her because she’s still incomplete.”

“Jesus Christ,” I said.

“Exactly,” Dr. Hilliard said.

The sunlight filtered in through the venetian blinds on the window above Dr. Hilliard’s desk. It splashed across Dr. Hilliard’s muted beige carpet.

“She’ll want to be rescued,” I said. “But she won’t like me for it.”

I sat still for a time rubbing the knuckles of my left hand along my chin. “But if I don’t rescue her…”

“Don’t misunderstand. She must be rescued. Duress is never positive. And everything I know of you suggests you are the best one to do it. I say all this only so that you will understand what may come afterward. If you succeed.”

“If I don’t succeed, I’ll be dead,” I said. “And the matter will be less pressing to me. Best plan for success.”

“I think so,” Dr. Hilliard said.

“I’ll rescue her from Costigan and she can then rescue herself from me.”

“As long as you understand that,” Dr. Hilliard said.

“I do.”

“And when she has rescued herself. If she chooses to be with you, do you want that?”

“Yes.”

“And Costigan does

n’t matter?”

“He matters,” I said. “But not as much as she does. She’s been doing the best she could, right from the start. He was something she had to do.”

“And you’ll forgive her?”

I shook my head. “Forgiveness has nothing to do with it.”

“What does have something to do with it?”

“Love,” I said.

“And need,” Dr. Hilliard said. “I too believe love. But you forget need only at great peril.”

“Frost,” I said.

Dr. Hilliard raised her eyebrows.

“‘Only where love and need are one,”’ I said.

“And the next line?” she said.

“‘And the work is play for mortal stakes,”’ I said.

She nodded. “Do you have eighty dollars, Mr. Spenser?”

“Yes.”

“That is what I charge an hour. If you pay me for this hour, I can make a defensible argument that you are a patient and that patient-doctor transactions are privileged.”

I gave her four twenties. She gave me a receipt. “I guess that means you’re not going to call the cops,” I said.

“It does,” she said.

“Anything else I can know?”

“Russell Costigan sounds like a man,” she said, “unhampered by morality or law.”

“Me too,” I said.

CHAPTER 16

WE BOUGHT A ROAD ATLAS IN A Waldenbooks on Market Street, and then we went to a flossy sporting goods store near the corner of O’Farrell and outfitted for our assault on the lodge.

To drive north from San Francisco you had your choice of the Golden Gate Bridge and the coast road, 101. Or the Oakland Bay Bridge and connection to Interstate 5. For people on the run toll bridges were bad places. Traffic slowed, and cops could stand there and look at you when you paid your toll. It was a favorite stakeout for cops.

A Savage Place s-8

A Savage Place s-8 Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil

Appaloosa / Resolution / Brimstone / Blue-Eyed Devil Perish Twice

Perish Twice Spare Change

Spare Change Family Honor

Family Honor Melancholy Baby

Melancholy Baby Chasing the Bear

Chasing the Bear Gunman's Rhapsody

Gunman's Rhapsody The Widening Gyre

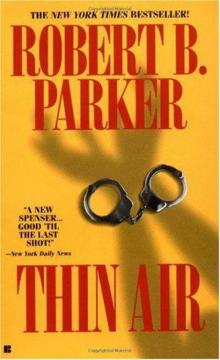

The Widening Gyre Thin Air

Thin Air Hundred-Dollar Baby

Hundred-Dollar Baby Double Deuce s-19

Double Deuce s-19 Appaloosa vcaeh-1

Appaloosa vcaeh-1 Potshot

Potshot Widow’s Walk s-29

Widow’s Walk s-29 Ceremony s-9

Ceremony s-9 Early Autumn

Early Autumn Walking Shadow s-21

Walking Shadow s-21 Death In Paradise js-3

Death In Paradise js-3 Shrink Rap

Shrink Rap Blue-Eyed Devil

Blue-Eyed Devil Perchance to Dream

Perchance to Dream Resolution vcaeh-2

Resolution vcaeh-2 Rough Weather

Rough Weather The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9

The Jesse Stone Novels 6-9 Cold Service s-32

Cold Service s-32 The Godwulf Manuscript

The Godwulf Manuscript Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6

Looking for Rachel Wallace s-6 Playmates s-16

Playmates s-16 School Days s-33

School Days s-33 Blue Screen

Blue Screen Crimson Joy

Crimson Joy Sea Change js-5

Sea Change js-5 Valediction s-11

Valediction s-11 Playmates

Playmates Back Story

Back Story Taming a Sea Horse

Taming a Sea Horse Hugger Mugger

Hugger Mugger Small Vices s-24

Small Vices s-24 Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel

Silent Night: A Spenser Holiday Novel Early Autumn s-7

Early Autumn s-7 Hugger Mugger s-27

Hugger Mugger s-27 (5/10) Sea Change

(5/10) Sea Change Now and Then

Now and Then Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6

Robert B. Parker: The Spencer Novels 1?6 Hush Money s-26

Hush Money s-26 Looking for Rachel Wallace

Looking for Rachel Wallace Night Passage

Night Passage Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes All Our Yesterdays

All Our Yesterdays Night and Day js-8

Night and Day js-8 Stranger in Paradise js-7

Stranger in Paradise js-7 Double Play

Double Play Crimson Joy s-15

Crimson Joy s-15 Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe

Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe Pastime

Pastime God Save the Child s-2

God Save the Child s-2 Bad Business

Bad Business Trouble in Paradise js-2

Trouble in Paradise js-2 Pastime s-18

Pastime s-18 The Judas Goat s-5

The Judas Goat s-5 School Days

School Days Death In Paradise

Death In Paradise Ceremony

Ceremony Paper Doll s-20

Paper Doll s-20 Brimstone vcaeh-3

Brimstone vcaeh-3 Mortal Stakes s-3

Mortal Stakes s-3 Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace

Spencer 06 - Looking for Rachel Wallace Taming a Sea Horse s-13

Taming a Sea Horse s-13 God Save the Child

God Save the Child Chance

Chance Passport To Peril hcc-57

Passport To Peril hcc-57 Promised Land

Promised Land Widow’s Walk

Widow’s Walk Small Vices

Small Vices Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5

Robert B Parker: The Jesse Stone Novels 1-5 Split Image js-9

Split Image js-9 Sudden Mischief s-25

Sudden Mischief s-25 Potshot s-28

Potshot s-28 Split Image

Split Image Sixkill s-40

Sixkill s-40 Mortal Stakes

Mortal Stakes Stardust

Stardust Stone Cold js-4

Stone Cold js-4 Painted Ladies s-39

Painted Ladies s-39 Cold Service

Cold Service Ironhorse

Ironhorse High Profile js-6

High Profile js-6 The Boxer and the Spy

The Boxer and the Spy Promised Land s-4

Promised Land s-4 Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Passport to Peril (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Painted Ladies

Painted Ladies Valediction

Valediction Chance s-23

Chance s-23 Double Deuce

Double Deuce Wilderness

Wilderness Sudden Mischief

Sudden Mischief Night Passage js-1

Night Passage js-1 A Catskill Eagle

A Catskill Eagle The Judas Goat

The Judas Goat Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow Pale Kings and Princes s-14

Pale Kings and Princes s-14 The Professional

The Professional Chasing the Bear s-37

Chasing the Bear s-37 Edenville Owls

Edenville Owls Sixkill

Sixkill A Catskill Eagle s-12

A Catskill Eagle s-12 A Savage Place

A Savage Place Now and Then s-35

Now and Then s-35 Five Classic Spenser Mysteries

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries Thin Air s-22

Thin Air s-22